Romney's Plan: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

To read Mitt Romney's economic plan is to join a more elevated conversation. This is a document written by people who value expertise, and it shows.

It avoids overstatements and misstatements. It credits Presidents Bush and Obama for pulling the financial system back from the brink in 2008-2009. While acknowledging the role of government policy in abetting the housing bubble, the report lays the blame for the excesses of the 00s on the bankers who committed them. The report does take some partisan jabs, but they meet the truth test.

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the non-partisan research organization that determines when business cycles begin and end, tells us that the Great Recession came to a conclusion in June 2009, when the economy technically returned to the path of growth. However, if the downdraft officially ended at that juncture, that assessment is almost an artifact of NBER’s definitions and nomenclature. For the Obama Recovery is different from its predecessors. As one team of economists has put it in the colorless language of their profession, “the path of adjustment [has] exhibited important departures from that seen during and after prior deep recessions.” In plain words, we are now more than two years into an economic recovery that has been one of the most lackluster in our nation’s history.

The document has one great excellence and two major failings.

The excellence is the focus on long-term economic growth. In his introduction to the plan, Columbia Business School Dean Glenn Hubbard remarks: "Robert Lucas, a Nobel laureate in economics, famously wrote that once one starts to think about economic growth, it is hard to think about anything else."

Achieving long-term growth is the most fundamental task of national economic management. Achieving long-term growth also happens to be the problem set to which conservatives bring their best answers. Romney's answers to the problem are as expected, but no less potent for their familiarity: keep taxes low and regulation predictable. Promote trade, while penalizing countries that manipulate their currency to subsidize exports to the detriment of US industry. Within the Republican tradition, he might have added more: invest in scientific research and basic infrastructure. Extra points for recognizing the importance of skilled immigration and rationalizing the corporate tax system in particular.

But here are the major failings, and they are serious.

A President Romney would take office in January 2013, at a time when even on a best-case scenario more than 10 million Americans will still be unemployed or under-employed, more than half of them for a very long time. What to do for them? On this urgent topic, the plan falls dismayingly quiet. Even if Romney's policies do raise the long-term growth rate of the United States beginning sometime about 2014, unemployment won't return to normal levels until a Romney second term. That portends almost a decade of very high unemployment.

Since the long-term unemployed tend to become unemployable, such a scenario portends that millions of Americans will likely never return to work at all. What to do about them? Put them on disability pensions? Create federal make-work programs? But the Romney plan calls for early and rapidly enlarging cuts to federal spending, militating against those two obvious answers. What then?

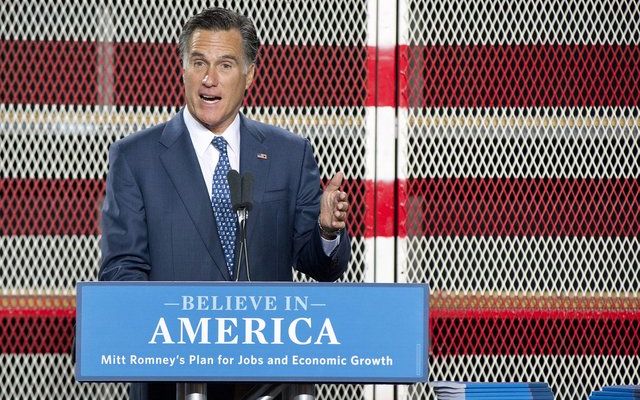

The second failing is illuminated by Mitt Romney's speech announcing his new plan. In the speech, Romney laid great stress on raising the incomes of middle-class Americans. Good! But as his adviser Glenn Hubbard can tell him with graphs and charts, the heaviest weight on middle-class incomes is the rise in the cost of employer-provided healthcare, which devoured every dime of extra employee compensation during the Bush years.

Until health care costs are controlled, it's again hard to see how wages can grow. So where's the plan for health-care cost control? It's a subject with which Mitt Romney is deeply familiar, to put it mildly.