God Does Not Play Baseball

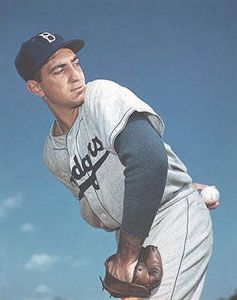

As if Jews haven’t suffered enough, it turns out that Ralph Branca is a member of our tribe. The man who served up Bobby Thompson’s Shot Heard Round The World in 1951 recently learned that his mother was a closeted Jew. The full story, told in poignant detail in a recent New York Times article by Joshua Prager, suggests that Branca’s hidden religion may have had major ramifications for baseball.

Thompson’s home run completed the miracle at Coogan’s Bluff, as the Dodgers squandered a 13.5 game lead and lost the National League pennant to the Giants in the most agonizing defeat in baseball history. But, you ask, what does that have to do with religion? According to Branca, everything. Prager quotes the pitcher as follows: “Maybe that’s why God was mad at me – that I didn’t practice my mother’s religion.” Prager observes that Branca was not joking, but rather is “a Job wondering about the root of his suffering.” As Branca elaborates, the almighty “made me throw that home run pitch. He made me get injured the next year. Remember, Jesus was a Jew.”

Good grief. If God’s vengeance over ballplayers’ religious practices determines the outcome of games, think of the ramifications for your next Fantasy draft. Stop studying players’ statistics and bone up on their church attendance. But seriously, “He made me throw that home run pitch?” God has a lot to answer for, but was he really the de facto losing pitcher in the 1951 playoff s? “He made me get injured the next year?” The Lord supposedly sees every sparrow, but does he really micromanage the DL? I’m not sure who should be more bothered by such silliness – believers or atheists.

I don’t want to come down too hard on Branca, by all accounts a good and decent man who paid a terrible price for our society’s excessive attachment to victory. (To add insult to injury, it turns out the Giants were stealing signs with a telescope and Thompson may have known what pitch was coming.) But his pop theology warrants notice because it typifies an emerging trend: athletes who believe God guides performance.

There were always a few ballplayers who crossed themselves before each at-bat and used the post-game press conference to attribute their every accomplishment to Jesus Christ. But such behavior is increasingly common. Note the proliferation of ballplayers who, upon completing their home run trot, point skyward in acknowledgement of the source of their power. Some players don’t reserve their gratitude for home runs – even a measly single triggers their skyward point.

Have we gone mad? If there is a God, she needs to have her head examined if she worries about the outcome of ballgames. Isn’t there enough trouble in the mid-east? Can’t she get to work on the economy?

As for Ralph Branca, there’s no shortage of people he can blame for the unfortunate turn his life took 60 years ago. If manager Charlie Dressen had made the shrewder move, and brought in ace reliever Clem Labine, the Dodgers probably would have won – or else Labine, not Branca, would have worn the goat horns. If the Giants hadn’t cheated, maybe Branca would have retired the side and the Dodgers moved on to the World Series. If Brooklyn weren’t obsessed with their Dodgers, Branca’s failure might have faded into the limbo of forgotten things. (Who remembers which pitcher yielded Bill Mazeroski’s home run that won Game 7 of the 1960 World Series?) But to blame God of all “people”?

This unjust attack on the deity is ultimately no different from all those players who share the credit for their base hits with the creator. The achievements and failures of athletes lie in themselves, not the stars. We can argue about the place of religion in the public square, but on the baseball diamond?