Buffett Tax Would Cover Seven Days Spending

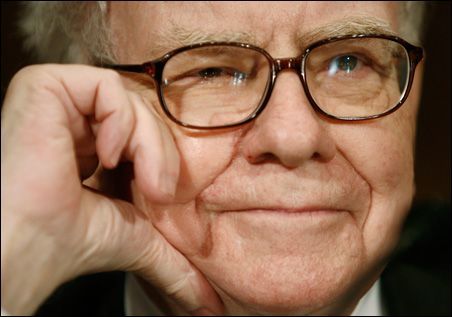

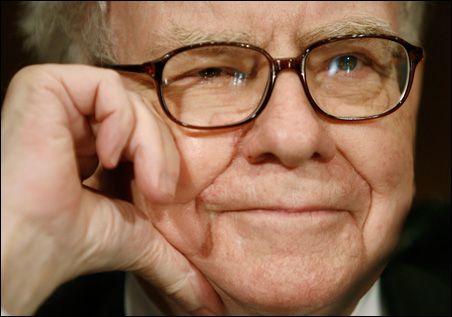

Warren Buffett is known as the Sage of Omaha for a good reason: his outstanding ability to find profitable investments that took him from a small portfolio owner to one of the richest people in the world.

Recently, he used his formidable reputation to suggest in the New York Times, Financial Post and an interview with Charlie Rose on PBS that the U.S. government should raise taxes on the 400 super-rich, who in 2008 together earned $90.9 billion and paid only on average 21.5 percent of it in taxes. That is lower than the average percentage paid by most middle-income Americans.

Buffett justifies his proposal on the grounds that the present tax system is unfair, parroting the mantra of tax-addicted interventionists and socialists everywhere. He said “It will not be pretty” in response to Rose’s question about what he thinks would happen in the United States if the present unfairness continues and unemployment remains high. What does he mean? Will there be riots in the streets or the proletariat rising to shed its shackles?

Buffett correctly notes that the proposed tax increases will do little to alleviate the present fiscal problems of the United States. If taxes on the super-rich were raised so that they paid not the present 21.5 percent but 50 percent of their incomes, revenues from the top 400 earners would go up by $26 billion (one half of $90.9 billion minus the present $19.5 billion). Since this year alone, the U.S. federal deficit will be around $1.4 trillion, or $3.8 billion a day, the new revenue would cover less than seven days of deficits.

The numbers are even worse for total federal spending. In 2010, that amounted to $3.6 trillion or $9.7 billion a day. Buffett’s new taxes up against that would be gone in just 2.7 days.

But these numbers are excessively optimistic because the amount raised by higher taxes is likely to be much smaller than $26 billion discussed above. That is because, as he notes, a large proportion of the total income of the super-rich comes from capital gains and financial trading, which is at the discretion of taxpayers.

The problem for the economy comes from the fact that higher taxes not only reduce total revenue, they also lock in capital and reduce the flow of funds into better investments and thus create smaller gains in productivity, income and employment.

Buffett indicates that this effect would be small or non-existent since the investment decisions he and his super-rich friends make are not affected by taxation. While this assertion flies in the face of everything we know about incentives, he could be right about his friends, but he forgets that there are many, important, small investors to whom he surely has not spoken.

These many small investors invest in risky new ventures and are the drivers of economic growth and employment. They know that only a few of them make it big but they are driven by the hope that they are among the few. In an important sense they are like the buyers of lottery tickets, who need much less skill than investors, but who buy more tickets when jackpots are large. The managers of lotteries certainly know this and advertise when the pots are large. Lower returns on investment and gambling through taxation will bring less investment and fewer ticket sales.

As well informed as Buffett is, he may be presumed to know about the role of incentives in motivating small investors who want to become super-rich, or at least rich. If he is, he has made the explicit, sage decision that living in a country with greater fairness in the distribution of the tax burden and after-tax income is worth the negative effects on productivity and employment that accompanies it. He would not be the first egalitarian to have done so.

But before Buffett’s ideas of higher taxes on the rich are put into place, there ought to be a public discussion of the size and merit of the trade-off between fairness and income. Such a discussion took place when John F. Kennedy was president and resulted in a dramatic lowering of top marginal tax rates that had been between 79 percent and 94 percent during the 1930s-1950s. In spite of Kennedy’s well-known concerns about fairness, the incentive and efficiency argument won.