Why Bush Didn't Mention Canada After 9/11

After the horror and grief of the 9/11 attacks came a distinctively Canadian after-shock: The jolt of a seeming direct insult to Canada by the president of the United States.

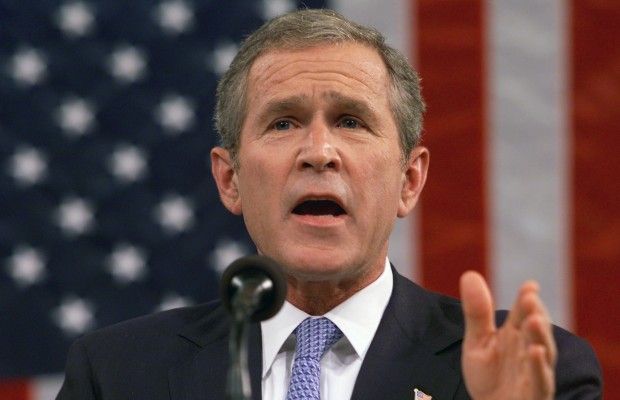

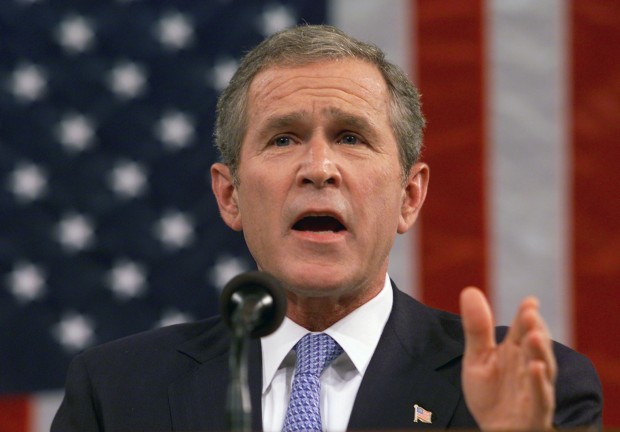

Nine days after the attacks, president George W. Bush addressed both houses of Congress. The president opened with thanks to nations around the world:

“America will never forget the sounds of our national anthem playing at Buckingham Palace, on the streets of Paris and at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate.” The president singled out South Korea, Egypt, Australia, Africa, Latin America, Pakistan, Israel, India, El Salvador, Iran, Mexico, Japan, and Britain for thanks, commendation or remembrance.

As Canadians watched, many wondered: El Salvador? Egypt? Iran? What about us?

More than 30,000 stranded American travelers found welcome in Canada after the terror attacks, 7,000 of them in one small city, Gander, N.L. As it was later observed by author Teri A. McIntyre:

Schools and halls quickly became emergency shelters. Residents invited people into their homes for showers, beds and meals. People stripped their houses bare of sheets and towels, and offered the use of their vehicles. Pharmacists filled prescriptions from all over the word at no cost. Local businesses emptied their shelves of food, clothing, toys and toiletries.

These acts of spontaneous individual kindness went unmentioned in the president’s speech. Canadians who had opened their homes and hearts reacted with anger to the apparent slight. And many Canadians believed they knew precisely who to blame: me.

I was working on 9/11 as a speechwriter and special assistant in the Bush White House. A rumor spread that I personally had been responsible for the omission of Canada, in some kind of outburst of Canadian self-loathing.

Over the next weeks, I was inundated by requests — challenges really — from Canadian media to explain the speech and defend myself.

I declined. When I emerged from the administration, I wrote a book about my experiences, but dealt only glancingly with Canada and the 9/20 speech. A decade later, and with the Bush administration receding into history, there seems no reason not to tell the story in full.

My speechwriting portfolio was economics. In those first days after the attacks, the president confronted a dizzying array of economic problems. The New York stock exchange was closed. The airline industry faced bankruptcy. The economy of the New York-New Jersey area had suffered a devastating blow. The already weak national economy teetered on the verge of severe recession. A new war had to be paid for, and terrorist finances had to be hunted around the globe.

Statements had to be prepared on all these issues for the president and other senior officials. Little of this work is remembered now, but it seemed very important at the time.

At the same time, all the White House speechwriters were called upon to write remarks to mourn the dead, name the guilty, and protect the innocent against wrongful accusations. On September 14, the president delivered a beautiful memorial address at the National Cathedral. The president visited a Washington mosque and repeatedly spoke against blaming all Muslims for the terrorist attacks.

The joint session speech was written by the same troika that had produced George W. Bush’s powerful convention speech in 2000: Michael Gerson, Matthew Scully and John McConnell, with a lot of input from communications director Karen Hughes.

Gerson, Scully and McConnell were and are supremely talented writers, although their partnership was already shadowed by animosities that would in time erupt into public view. But the Bush White House, even more than most White Houses, was focused inward, isolated from the rest of the world, even the rest of the U.S. government.

Scully and I shared an office, a once grand room in the Executive Office Building now bisected by a paper-thin partition wall, and we became and remained good friends. In the commotion and turmoil of those 18-hour days — with all of us expecting at any moment to be killed by a car bomb on Pennsylvania Avenue — even close friends found precious few seconds to talk.

I reconnected with the joint-session speech on the morning it was to be delivered. My eyes bulged as I read the opening acknowledgments. I raced to see Gerson to warn that the reaction in Canada would be large and angry.

What the hell happened, anyway? I wanted to know. Was this some kind of payback to Jean Chretien? (The Bush-Chretien relationship was notoriously poor.) If so, please remember that 60% of Canadians did not vote for Jean Chretien. Why insult them?

No, no, no came the answer. It wasn’t that at all, it wasn’t personal.

Well what was it then?

Gerson shuffled in embarrassment. “We just … forgot.”

We have to fix this, I pleaded.

It’s too late, he answered. The president has signed off on the text. Evidently the president had forgotten too.

Let’s reopen the text, I urged. Futile. Bush was adamant in his demand for an orderly and conclusive speech process, unlike the endless rewrites of the Clinton White House. Once a speech was deemed closed — it was closed.

I returned home that night depressed and demoralized. As my wife and I prepared to watch the speech, I gloomily predicted to her that the Canadian reaction would be savage — and that I’d get the blame.

She countered: “If that happens, why not just tell them truth?”

To this day, she quotes the reply I gave her all those years ago: “Is the truth really better?”

Originally published in the National Post.