The Ugly Truth About the American Dream

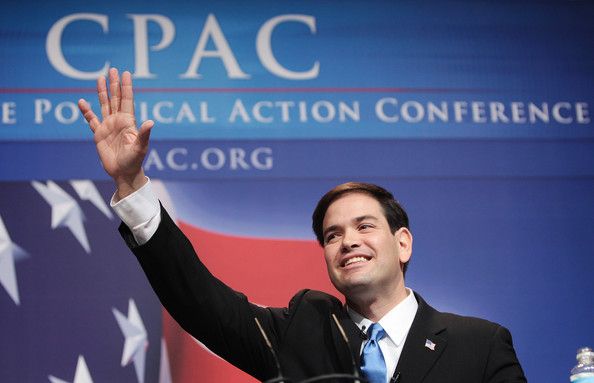

The promise of upward economic mobility is central to the American Dream. Marco Rubio invoked it at CPAC in 2010 with stirring language:

[America is] the only place in the world where it doesn't matter who your parents were or where you came from. You can be anything you are willing to work hard to be. The result is the only economy in the world where poor people with a better idea and a strong work ethic can compete and succeed against rich people in the marketplace and competition. And the result is the most reliable defender of freedom in the history of the world.

This is critical to the conservative narrative about America and it justifies many of the policies which call for a less active government. Unfortunately, the truth is does not match the rhetoric. It turns that the American Dream of upward mobility is not equally within reach of everyone.

The Pew Economic Mobility Project has published a new study which looked at the factors which lead to downward mobility.

Previous research helped to lay out the broad contours of what is known about economic mobility. A 2008 Pew report discussed the lack of economic mobility among African Americans:

A startling 45 percent of black children whose parents were solidly middle income end up falling to the bottom income quintile, while only 16 percent of white children born to parents in the middle make this descent.

Similar trends are found in other income groups as well. In another disturbing example, 48 percent of black children and 20 percent of white children descend from the second-to-bottom income group to the bottom income group. In addition, black children who start at the bottom are more likely to remain there than white children (54 percent compared to 31 percent).

The 2011 study (which used a different sample group) wanted to ask a broader question: what factors are causing this to occur? The study looked at different measures of absolute and relative income inequality and determined which factors were the most significant in downward mobility.

img class="alignnone size-full wp-image-103790" title="Economic Mobility" src="/files/wxrimport/2011-09/economic-mobility.jpg" alt="" width="622" height="447" /><

(One of several charts associated with the story, the rest can be seen here.)

Pew's Economic Mobility Project Manager Erin Currier explained to FrumForum that the factors which had the most impact in determining downward mobility were levels of education and whether or not individuals got and stayed married. While perhaps not unexpected or controversial findings, the report underscores the importance of these factors. As Currier explains:

Regardless of how we measured downward mobility ... we see the same pattern emerging. Post-secondary education and higher educational attainment matters, no matter how you measure downward mobility. This is a key reason why some people might be able to maintain their middle class status and some may not.

The second key finding is that marital status is a key piece that explains why people stay in the middle class or fall out of it.

In this current generation of adults, we have seen a huge increase in two-earner familier. It's very important for family incomes that woman have entered the labor market.

When you look at people who become divorce, separated, or who are never married, it’s less surprising that they would have less of a chance of staying in the middle class than someone who is married.

While this is not surprising, it is helpful to be reminded of what can undermine upward mobility, and not simply to assume that upward mobility is equally likely for everyone, or even worse, to trot out blasé arguments that the poor in America are at least fortunate enough to own microwaves and cable TV.