The Problems With Stiglitz's Depression

What is wrong with Joe Stiglitz's analysis of the Great Depression? Click here for Part 1.

Problem 1: Repeat after me - The Great Depression was a global event. That's a fact American economic historians always have great trouble keeping in mind, and Stiglitz here succumbs to the national myopia.

How did the troubles of the American farmer wreck every economy from Germany to China? If your theory of the Depression does not start with the huge debts bequeathed by the First World War - and the failure of the postwar settlement to re-establish a stable economic and financial order - then it's not a very good theory.

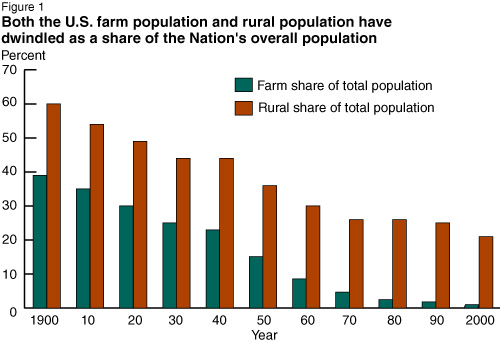

Problem 2: So here's the chart of the decline of farm employment.

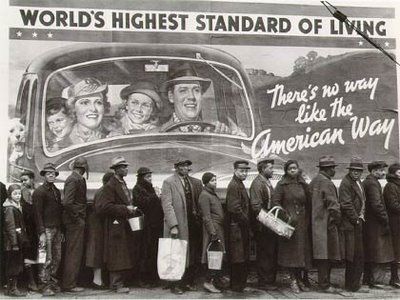

The question that's bound to occur is: Do these farmers look trapped to you? Between 1900 and 1930, the farm share of the population declines on a steady glidepath. There look to be abundant opportunities elsewhere. We can import into our chart some of our knowledge of US history: migration from the farm was certainly easier for whites than for blacks. Perhaps it makes sense to think of Southern black sharecroppers as "trapped." (The unusually sharp drop in the farm population between 1940 and 1960 represents the great migration of Southern black farmworkers to industrial cities.) But poor black sharecroppers were hardly in a position to accumulate significant debt in the 1920s. Nor is it plausible to describe the decline in their consumption from pitifully little in 1928 to miserably less in 1930 as an important constraint on overall economic demand in the US economy.

Problem 3:

If "trapped industrial workers" are the reason for today's deep and protracted unemployment, why was the plunge in employment deepest and most protracted in Nevada, South Carolina, Florida and California? The Rustbowl suffered its most painful shocks between 1974 and 1993. If Stiglitz's story is true, why did we not see deep and prolonged unemployment in the 1990s and 2000s, closer in time to the steepest drops in industrial employment?

Perhaps Stiglitz has in mind a story like this: Dad loses his steelworking job in Youngstown, Ohio, and subsists thereafter on a disability pension. Junior graduates from high school in Youngstown, finds work in the homebuilding industry in Florida - but is now stranded by the collapse of the housing market. Some verion of that story probably applies to a large number of people, but how is it a story of "entrapped" labor? Isn't it a story of labor flexibility - manufacturing to construction? Yes, perhaps Junior's life history tells us something about the shrinking prospects for less-skilled workers. But that's a different narrative from the narrative that Stiglitz wants to tell.

Problem 4:

Stiglitz's critique of Obama administration policy reminds me of the old law school joke, "Right result, wrong reason." Even as he rejects the administration's theory of its actions, he calls for extra doses of exactly the same policies.

The only way it will happen is through a government stimulus designed not to preserve the old economy but to focus instead on creating a new one. We have to transition out of manufacturing and into services that people want—into productive activities that increase living standards, not those that increase risk and inequality. To that end, there are many high-return investments we can make. Education is a crucial one—a highly educated population is a fundamental driver of economic growth. Support is needed for basic research. Government investment in earlier decades—for instance, to develop the Internet and biotechnology—helped fuel economic growth. Without investment in basic research, what will fuel the next spurt of innovation? Meanwhile, the states could certainly use federal help in closing budget shortfalls. Long-term economic growth at our current rates of resource consumption is impossible, so funding research, skilled technicians, and initiatives for cleaner and more efficient energy production will not only help us out of the recession but also build a robust economy for decades. Finally, our decaying infrastructure, from roads and railroads to levees and power plants, is a prime target for profitable investment.

It's a familiar program, exactly the program that President Obama laid out in his Kansas speech last month, subject to all the same objections. The US has doubled K-12 spending since the early 1990s. What do Americans have to show for it? Who believes that even more spending will buy better results? What results have been bought by the rising per-student cost of higher education? Yes, we can improve the job statistics (at least for a time) by putting more people on the government payroll at relatively high wages. But as Tony Blair and Gordon Brown too painfully demonstrated in the UK between 1997 and 2008, their government-led employment did not translate into higher productivity, but only into a heavier debt load for taxpayers to sustain when their own incomes are dropping. As for direct government investment in energy technology, one can only say ... sigh. Birde sizlere ek olarak sunulan

- MORE TO COME -