The Hidden Costs of Silly Lawsuits

Recently, a Utah woman filed suit against Google after following their online mapping directions onto a highway, where she was hit by a car.

Recently, a Utah woman filed suit against Google after following their online mapping directions onto a highway, where she was hit by a car.

A new name can be inducted on the Wall of Fame for frivolous lawsuits: Lauren Rosenberg. Rosenberg is suing Google because she used the popular Google Maps service to get walking directions around Park City, Utah. The directions advised her to walk on a highway with no pedestrian path. While she was walking on it, a car struck her. Rosenberg joins a very special class of plaintiffs occupied by Stella Liebeck and Roy L. Pearson. Liebeck sued McDonald’s because she spilled hot coffee on her lap while driving and Pearson sued a D.C. dry cleaner for $65 million because they lost his trousers.

Most Americans think these are the cases that demand tort reform -- they are sensational and ridiculous. In reality, these attention-grabbing lawsuits are just small parts of a larger problem. The U.S. legal system operates under a set of perverse incentives and outdated rules. Unless significant changes are made to rules that haven't been updated since 1938, America’s economic competitiveness will decrease.

A new survey of Fortune 200 Companies by three business and lawyer groups (Lawyers for Civil Justice, the Civil Justice Reform Group, and the U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform) has given the first empirical evidence that litigation costs have increased significantly. Of all the pieces of data assembled, three stand out: the high cost of litigation, the way it makes America less competitive, and the inefficiencies of the process.

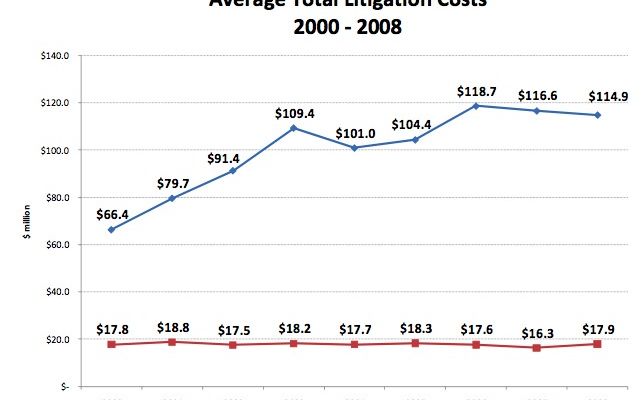

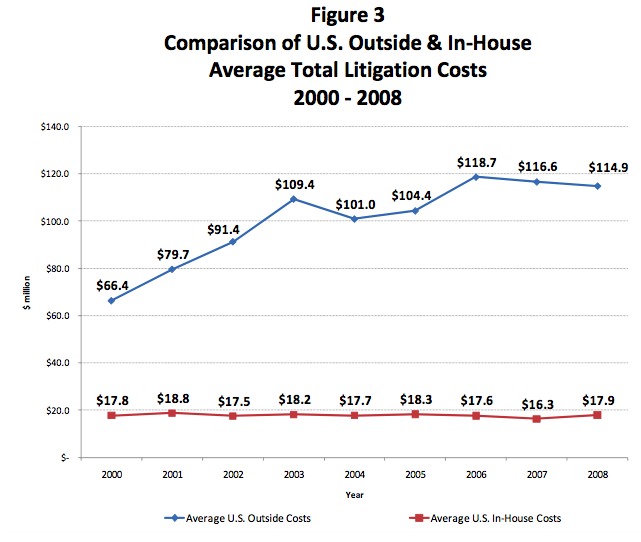

First, average outside litigation costs have consistently gone up by roughly 9% a year since the year 2000. After almost a decade, the average cost has nearly doubled. Meanwhile, lawyer salaries and retainers have stayed consistent. From this data, it is clear that on the whole, lawsuits have become more expensive:

Source: Litigation Cost Survey of Major Companies

Source: Litigation Cost Survey of Major Companies

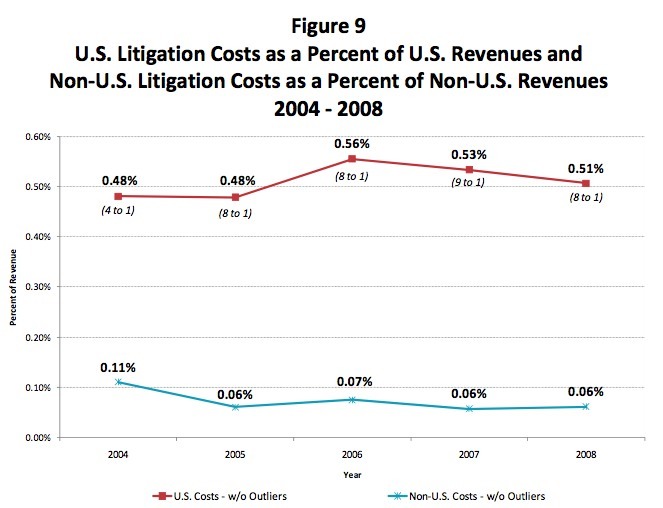

This is discouraging, but how do these costs compare with the rest of the world? It turns out that as a percentage of revenue, U.S. companies can spend nine times as much on litigation in the U.S. then they do in other countries.

Source: Litigation Cost Survey of Major Companies

Source: Litigation Cost Survey of Major Companies

These higher costs are not resulting in greater efficiency. The U.S. legal system allows for plaintiffs to request as many documents as deemed necessary from the defendant for the trial. This “discovery” process is supposed to bring to light facts that are relevant to the case. This is not happening. As the survey notes:

In 2008, for example, 4,980,441 pages of documents were produced on average in discovery in major cases that went to trial. However, the average number of exhibit pages totaled 4,772, or 0.10 percent of pages produced. This reflects a ratio of 1,044 to 1.

The “discovery” process is not being used to assemble facts; it is being used to force the defendants to make a choice: either pay a settlement and end the lawsuit without a proper trial, or pay excessive costs to retrieve more documents at the whims of the plaintiff.

This is not the way it has to be. The U.S. legal system is operating under a set of rules that have not been significantly modified since 1938. Under the current set of rules, if a judge does not rule a lawsuit to be frivolous, the plaintiff can request the defendants to provide any and all documents that they think are necessary. Because of recent advancements in computer technology, the quantities of documents that can be requested have also increased.

Al Cortese, counsel for Lawyers for Civil Justice, summarized the current state of the legal system: “The system essentially says that a plaintiff can come into court, plead nothing, discover everything, at no cost, and drive business (which does not want to spend that sort of money on litigation) to settle a case.” If Lauren Rosenberg doesn’t get her case thrown out as frivolous, she will get to request that Google provide millions of documents so that she can attempt to prove that it was not her own fault that she walked onto a highway without pedestrian walkways.

The process for changing these rules is slow but thorough. The Judicial Conference will have to recommend changes be made to the federal rules of practice, before going to the Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court approves then, they go to Congress under the Rules Enabling Act. If Congress doesn’t act or veto the changes, they automatically become law.

It may take years for the U.S. to reform its legal system into something that can be described as efficient and cost-effective, but this empirical study will give much needed ammunition for advocates of tort reform. It should give defenders of the status quo (as well as advocates for making it even easier for plaintiffs to make demands of defendants) pause. This is not a system worthy of endorsing.