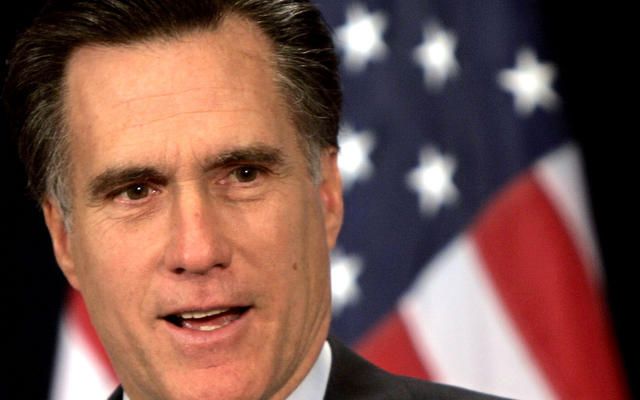

The Case for Romney

In my column for The Week, I make the affirmative case for Mitt Romney to be the Republican presidential nominee:

For three years, Republican activists, strategists, and donors have tried to find a plausible alternative to Romney, and again and again they have failed. For about 15 minutes, that alternative seemed at last to have materialized in the form of Texas Gov. Rick Perry.

Perry still leads the national polls and is still raising money. Yet it's hard to miss the loud hiss of air escaping this particular balloon.

So maybe it's time to reconsider the long-standing frontrunner — the candidate who was more than conservative enough for party conservatives back in 2008 — and to rediscover his good points.

1) Given the dreadful economic conditions, the Democrats will have no choice in 2012 but to run a negative campaign against the Republican alternative. Message: "We may have disappointed you on jobs, but they will take away your Medicare, Social Security, and unemployment insurance."

Of all the Republicans in the field, Romney is least vulnerable to this line of attack. He did not associate himself with the Ryan plan to withdraw the Medicare guarantee from people under age 55. He did not denounce Social Security as a "monstrous lie." He has not condemned the unemployed as lay-abouts.

Yes, Romney has vulnerabilities of his own in a general election, plenty of them. But at least he is not adding more. Perry, on the other hand, generates new raw material for Democratic attack ads almost every time he opens his mouth.

2) After the campaign comes the presidency. Who can believe that Rick Perry has the wherewithal to do that job? The global financial crisis still rages about us. Just ahead: Debt defaults in Europe. After that? Perhaps the popping of China's real-estate bubble. What else? Who knows?

The person you want in that job in such a time is someone with a deep understanding of finance and economics. The U.S. is paying dearly now for electing in 2008 a president who lacked such understanding, despite many other fine qualities. As a result (as Ron Suskind now reports), economic decision-making in the Obama White House degenerated into a struggle between advisers to sway a more or less passive president.

Romney spent much of his career in financial markets. One benefit of that experience: He is less likely to be overawed by possibly self-interested actors than a less familiar president. The U.S. has had quite enough of that.

Click here to read the full column.