That Was Me Who Interrupted Your Dinner

While I waited outside the building for the second round of interviewing for my first real job, I saw a man get into a fight with a homeless drug addict. I was 17 years old. After I had gotten the job, I sat down at my desk. And in the cubicle next to me was the same man who had downed the vagabond. I was working as a telemarketer, selling newspaper subscriptions from an office in one of Toronto's most dangerous neighborhoods.

I quit after a few weeks, and found work in a trendy clothing store, surrounded by pretty girls who, on more than one occasion, nearly had me fired for creating a heartbroken work environment.

Back then, I was about to start college in the fall with my then-girlfriend, and things were looking wonderful. As I sat in my first lecture, and saw we would be studying The Great Gatsby in the spring, I looked back at my first job, thinking how sad it was and how I would never have to go back to work like that. I’d be “university educated!”

I'm about to go into my senior year, and The Great Gatsby is still one of my favorite books. In fact, I bring it to work every day so that I have something to read on my break and take my mind off things. You see, I'm working at that telemarketing place again, and nothing has changed except me.

The interview process was the same. The video they showed us (circa late 1990s) was the same. My pay, $10.25 per hour plus a measly commission, was the same. And the people were the same: immigrants from the Third World, people with faces cracked like bark who reek of Old English, and Somali women trying to put themselves through community colleges that advertise on television. And the product we sold, newspaper subscriptions, was the same. The only tangible difference in the company is that demand for paper subscriptions has shot down dramatically since I worked there last.

As then, I come into work at four every day and sit at my desk. The office is gray, the cubicles are gray, and even my supervisors' clothes are gray. Their faces too, and their hungry eyes as they stare at the shapely, shy young women from Nairobi who come in looking for work. The room is windowless, and all the cubicles are devoid of personal effects. No one seems to speak to each other.

Telemarketing goes along the lines of,“If I've met you one day, you might be gone the next. If you've met me, I might gone tomorrow.” It has one of the highest turnover rates of any job, and more often than not, you'll be fired for not having made a sale for a few days straight.

So how does one reach his quota? Our supervisors say skill and talent, and to a certain degree, that is true. But the fact of the matter is that selling over the phone is more a game of roulette than poker; it almost certainly depends on who picks up your call.

My first sale was pure luck. I happened to come across a brash woman who wanted a subscription even before I gave her my pitch. Another person in a small town said to me, “You're a good salesman, but you better try it on somebody else.” I did, and the next person laughed. “You almost sound pre-recorded, but you better try elsewhere, honey.” Elsewhere is usually the sound of a phone slamming in your ear, or a fed-up wife (because you have to push, my superiors say) getting her husband to yell obscenities until you apologize and hang up.

If telemarketing happened over Skype and the potential customers could see the sad faces of the salespeople, I'm sure we'd see a huge increase in subscriptions.

The general perception is that telemarketers have lousy or menial jobs; as I've said, people constantly mistreat them, or slam the phone in their faces. But as a telemarketer, you realize there's something else that gnaws at you whenever you come into work: you're expected to be a machine.

Telemarketing is based on a script. Veer away from the script, and you'll get a serious talking-to by your supervisor. You begin with the same introduction every time, “Hello, this is Name calling on behalf of Newspaper X. How are you today?” and continue until the customer cuts you off, or, more often than not, turns you off. In the former case, he’ll respond with something along the lines of “I read the news online” or “I already subscribe to another paper.” But don't worry! You won't have to think up an answer! Because in such circumstances, the script provides the telemarketer with the appropriate, company-decided response.

Regardless of how feeble it may seem to you, or however you think you can improve on it, you're made to follow it. There is no room for creativity or individualism in telemarketing; I'm not exaggerating when I say a machine could do this job—and in many cases, now do. After a couple of shifts, you won't even need the script anymore; the words are burnt onto your tongue.

To give you an idea of how many times you'll say the same thing over and over again, my supervisor told me our office calls about twelve and half million households within the span of twelve months. That means, we each call about a hundred and fifty people an hour; that’s twelve hundred a day. Some are faulty numbers, others answering machines, many are immediate hang-ups. But regardless, this is the truly grueling part of telemarketing: the constant repetition.

Sometimes, you won't get past the first sentence of your pitch. Other times, you'll have spent three minutes talking only to have the person say “Sorry, not interested” and then hang-up. I might be wrong in saying this, but some people seem to enjoy wasting a telemarketer's time. People tend to hate telemarketers, but what they forget is that, as annoying as they may be, they don't mean to be. They're people trying to make a living, and if they insist on you buying their product, it's only because their supervisor is breathing down their neck, dangling a noose alongside a quota chit.

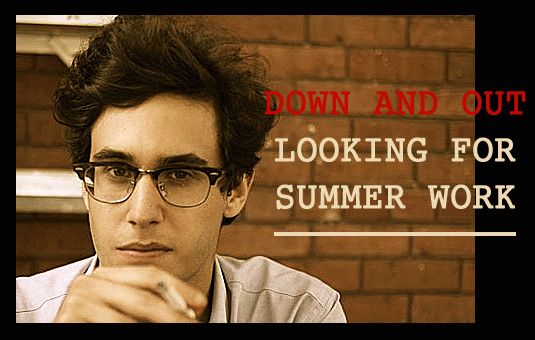

Over the course of this summer, I had tried time and time again to find real work. Telemarketing, where they say “come back anytime”, was always a back-up. But a back-up that seemed more like a step-back, and as such, highly improbable. Surely, I could find better work. But I obviously didn't, and I'm not exaggerating when I say the work here isn't only embarrassing, but downright depressing.

Some people may get used to it. But after years studying the flower-wreathed passages of Wharton, or the golden glories of ancient Rome, life suddenly becomes harsh when you sit next to someone with almost no teeth and what looks like steel wool for hair. Surely I could do better than this?

Daniel Portoraro, 21, is a senior at the University of Toronto, majoring in English. This is the third in his five-part series of trying to find summer work in a tough economy.