Taxing America's Expats Away

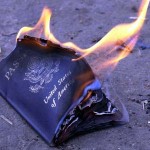

On Sunday, the New York Times reported that record numbers of Americans living abroad have renounced their citizenship. The Times did not mention that there is new legislation being considered that would further target the incomes of expatriate Americans. The article also neglected to point out that excessively taxing citizens to the point where they renounce their citizenship has been a bipartisan affair.

Most countries only require their citizens to pay income tax for the country they are working in. A British citizen working in Germany will only pay German income tax. Americans pay income taxes for both the country they are working in and the United States. Most developed countries do not do this, but it does put the United States in the same league as North Korea, the only other nation that practices this double taxation.

Expatriates used to have ways to mitigate this burden. The tax code has some income exclusions that only began to double tax Americans if they cross a high-income threshold. Companies that send Americans abroad have the option to tax equalize their employees wages, paying extra so that the employee would only have to pay roughly the same amount that they would of U.S. taxes.

Yet Republicans and Democrats have worked to raise expatriate taxes and complicate their filing process. In 2006, Republican Senator Chuck Grassley authored a significant change to the code that increased the tax on expatriates. As The Economist noted, it was “the Republican Congress's first renunciation of its widely trumpeted vow to block any increase in personal income taxes.” Further restrictions on foreign owned bank accounts came from the 2010 Bank Security Act.

According to Steven Relis, a Certified Public Accountant for a firm specializing on taxation of U.S. expatriates, the burden on these taxes is significant: “the 2006 tax law change increased the effective tax rate on income that was in excess of the exclusion and reduced the benefits of the housing exclusion.”

The Times described the process of renouncing citizenship as “relatively simple” but Relis points out that this ignores the scrutiny Americans face when they want to renounce their citizenship, “the IRS will assume that if a U.S. citizen wants to renounce their citizenship, that the only purpose for doing so is for tax evasion, therefore many clients opt to remain citizens.” Because of the complications, many Americans living abroad are genuinely unaware that they are not in compliance with the Tax Code.

The latest attempt to increase taxes on American expatriates is in the text of the “Tax Fairness and Simplification Act” introduced by Democrat Senator Ron Wyden and Republican Senator Judd Gregg. The bill would entirely remove the “foreign earned income exclusion” one of the few parts of the law that mitigates for double taxation.

Some may think that attacks on double taxation are just a conservative knee-jerk reaction to an attempt to raise taxes. As Jonathan Chait wrote on tax day:

Let me give you a hint, pouting rich people: We're not falling for your bluff. None of you is really going to quit your job and deny the world your precious genius because the Democrats raised your top tax bracket to 39.6%. That's because earning more than a quarter million dollars a year and having to pay a slightly higher tax rate than the average person is not actually such a horrible fate.

Yet in the case of expatriates, the empirical evidence suggests this is exactly what is happening! We can also assume that the majority of expatriates who do not renounce their citizenship are either eventually returning to the states, or trying to avoid the IRS.

Americans who live abroad surely owe some income tax to their mother country, the American military underwrites the global security that lets Americans work in foreign countries such as Japan and it is only fair to help support that. Yet surely we can agree that we should not promote a tax code which is increasingly discouraging Americans from remaining citizens.

UPDATED: Some commentators seem genuinely unaware that this is an issue of grave concern among the expatriate community. While there is a debate to be had over what an expatriate’s fair burden of taxes is, it is simply inaccurate to assume that this is not an issue.

When interviewed about expatriate taxes, Steve Relis, a CPA who specializes in expatriate tax returns, explained what some of the mitigating factors were:

The US offers US taxpayers an earned income exclusion for being either a bona fide resident of another country or being physically present in a foreign country for at least 330 days of a year. In fact if a US citizen working abroad earned less than $100,750 in 2009, there would be no US tax due.

This sounds acceptable, but the devil is in the details.

As noted in the article, if the Wyden-Gregg tax reform law truly gets rid of the earned income tax exclusion, a lot of these mitigating factors would likely vanish.

As other commentators have also noted, the cost of living in some European countries as well other nations such as Japan, mean that expatriates with a family living abroad may need more $100,750. This is especially true when you consider how many members of the expatriate community tend to have families and want to send their children to English speaking schools, which tend to be private and more expensive.

Additionally, the residency issues can be highly complicated. I am personally aware of expatriates who “worked” in Indonesia, but Indonesia’s own laws meant that foreigners could not be residents there, so they likely had to take up residency in neighboring countries such as Singapore. I dread to know the costs and difficulties their accountants faced while trying to figure out the Indonesian, Singaporean, and American taxes that their clients owed.

Those who want a more detailed explanation of the tax problems can be referred to this 2006 New York Times article on the costs of Senator Grassley’s changes to the expatriate tax code. Note that even in cases where an individual expatriate’s tax burden may not increase significantly, that the cost of supporting the expatriate is likely to be borne by the company that sends him abroad. This directly affects our competitiveness and discourages companies from sending Americans to work abroad.

Finally, when there is empirical evidence that more then 500 Americans have renounced their citizenship in just the first quarter of 2010, and when we know that there are many other requests being held up in consulates, surely they are responding to some negative incentives.

In 2008 The Economist also wrote about the challenges of Americans seeking to renounce their citizenship.

Follow Noah Kristula-Green on Twitter: @noahkgreen