Signs of Hope, Part 5

Make sure to read previous entries in the 'Signs of Hope' series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

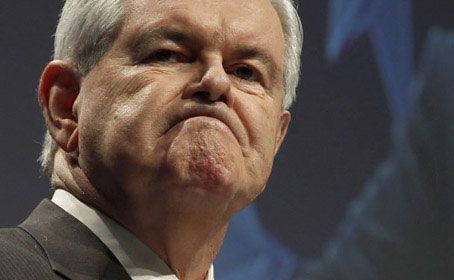

As Newt Gingrich surges in the polls in Iowa and other early primary states, several leading conservative columnists are explaining why Gingrich should be rejected by Republicans voters. Their arguments deserve a wider audience.

Ramesh Ponnuru:

Gingrich’s fans say that he isn’t the same man he was then; he has “matured” in his 60s. Maybe so. But he’s still erratic: This year he flip-flopped three times on the top issue of the day, the House Republican plan to reform Medicare. He’s still undisciplined: He went on a vacation cruise at the start of his campaign. He still has the same old grandiosity: In recent weeks he has compared himself to Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher and said confidently that the nomination was his.

He still has the same need to justify his every petty move by reference to some grand theory. Plenty of politicians competing in Iowa come out for ethanol subsidies; only Gingrich would proclaim that in doing so he was standing up to city slickers in a culture war invented in his own mind. He still has a casual relationship with the truth. In recent weeks he has said that Freddie Mac (FMCC) paid him to condemn its business model, only for reporters and bloggers to find out that he had in fact shilled for the organization in return for about $1.6 million.

He still has the same penchant for sharing whatever revelation has just struck him, as with his recent musings about getting rid of child-labor laws. “He goes off the deep end and throws things out there,” says Joe McQuaid, the publisher of the Manchester Union Leader, which has endorsed Gingrich. He means it as a compliment, but it doesn’t strike me as one of the top traits to seek in a president. Many voters may have the same reaction.

John Podhoretz:

We remember him going through one of the great political flameouts of our time — first helping to engineer the 1994 GOP takeover of Congress, then resigning after the 1998 midterms.

We remember the brilliant political design of the Contract with America — and how little of it actually made it into law. That would prove to be very much the pattern with Gingrich, who loves to think in grand terms but who tends toward not grandeur as a result but grandiosity, instead.

We remember how he tarnished his own “Republican revolution” even before it started between the 1994 election and the swearing-in of the new Congress by getting himself a $4.5 million book deal (that would be $6.5 million today) — a PR blunder and possible ethics violation that backfired so badly that he had to forswear his advance.

We remember the wildly wrongheaded conviction some of us shared with him that he was powerful enough to go mano a mano with Bill Clinton in 1995 — because he and we hadn’t taken account of the fact that in his races for his House seat, he’d get 100,000 votes while Clinton in 1992 got 40 million.

We remember how that conviction led to perhaps the greatest political blunder of our time — the showdown over the budget in October 1995 that led to the three-week government shutdown and the subsequent GOP cave-in that brought the “Republican revolution” to an end only nine months after it began.

We remember how, by 1997, Republican members of Congress who had once believed they owed him everything actively plotted a coup to remove him from the speakership.

We remember the fact that he led the moralistic charge against Clinton in 1998 — notwithstanding the fact that he himself was having an extramarital affair at the time.

And we remember things from after his time in office, like how he opposed the 2006 “surge” that turned around the Iraq war.

George Will:

Gingrich, however, embodies the vanity and rapacity that make modern Washington repulsive. And there is his anti-conservative confidence that he has a comprehensive explanation of, and plan to perfect, everything.

Granted, his grandiose rhetoric celebrating his “transformative” self is entertaining: Recently he compared his revival of his campaign to Sam Walton’s and Ray Kroc’s creations of Wal-Mart and McDonald’s, two of America’s largest private-sector employers. There is almost artistic vulgarity in Gingrich’s unrepented role as a hired larynx for interests profiting from such government follies as ethanol and cheap mortgages. His Olympian sense of exemption from standards and logic allowed him, fresh from pocketing $1.6 million from Freddie Mac (for services as a “historian”), to say, “If you want to put people in jail,” look at “the politicians who profited from” Washington’s environment.

His temperament — intellectual hubris distilled — makes him blown about by gusts of enthusiasm for intellectual fads, from 1990s futurism to “Lean Six Sigma” today. On Election Eve 1994, he said a disturbed South Carolina mother drowning her children “vividly reminds” Americans “how sick the society is getting, and how much we need to change things. . . . The only way you get change is to vote Republican.” Compare this grotesque opportunism — tarted up as sociology — with his devious recasting of it in a letter to the Nov. 18, 1994, Wall Street Journal (http://bit.ly/vFbjAk). And remember his recent swoon over the theory that “Kenyan, anti-colonial” thinking explains Barack Obama.

Gingrich, who would have made a marvelous Marxist, believes everything is related to everything else and only he understands how. Conservatism, in contrast, is both cause and effect of modesty about understanding society’s complexities, controlling its trajectory and improving upon its spontaneous order. Conservatism inoculates against the hubristic volatility that Gingrich exemplifies and Genesis deplores: “Unstable as water, thou shalt not excel.”