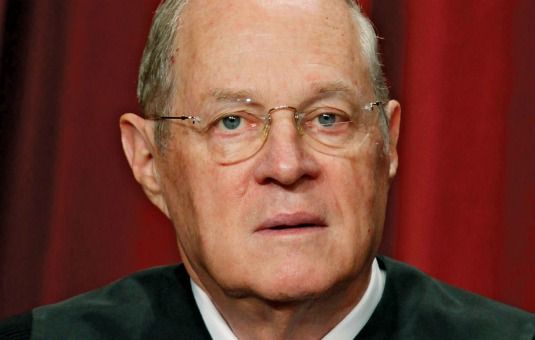

Res Judicata: Anthony Kennedy, The Unprincipled Justice

The brewing controversy about President Obama’s healthcare law means that the case will end up in the Supreme Court. One appellate court has upheld the constitutionality of the law (by a 2-1 vote) and another has struck it down (by a 2-1 vote).

Splits on appellate panels are rare. Two split opinions on the same question are even rarer, maybe unprecedented. Within the next month a third appellate court will issue its opinion. Then the Supreme Court will be petitioned to take these cases and decide whether the federal government has the constitutional authority to mandate people to buy health insurance.

Very intelligent people, judges on the two courts as well as scholars have come down on both sides of the question. This tells us that there is no clear answer. The founding fathers did not anticipate that Congress would pass a bill requiring citizens to do anything except pay certain enumerated types of taxes. (The income tax was not one of them and was declared unconstitutional. It took a progressive president, Woodrow Wilson, who passionately believed in enhanced federal government power and two-thirds of the state legislatures to enact the 16th Amendment allowing a federal income tax.) The Supreme Court once took a fairly narrow interpretation of the commerce clause, rejecting the arguments that it allowed many New Deal government programs. Then, as we know, the switch in time saved nine, and the Court shifted. Suddenly, the commerce clause (allowing federal regulation of “interstate” commerce) grew exponentially. A few months later the Court upheld a federal law regulating the production and pricing of wheat grown by a farmer for his own consumption (Wickard v. Filburn). This was a political shift. It was not based on any new material unearthed from the Constitutional Convention.

I think I know what the framers meant by “interstate” commerce. Yet there isn’t enough direct evidence to persuade people holding different views. This does not mean we should feel free to interpret the Constitution subjectively. It means there is no single empirically correct interpretation that can command a majority. We are doomed to keep fighting over what the Constitution means.

Right now the Court is split 4-4 on what I like to think of originalist versus outcome-based decision making. Four justices (we know who they are), will vote to uphold the health care law as an appropriate exercise of federal power under the commerce clause of the Constitution. Those four justices would vote to uphold anything as an appropriate exercise of congressional power under the commerce clause (and if that won’t suffice, the all-purpose “necessary and proper” clause will do just fine). Their jurisprudence is not based on original intent or any decision before 1937. We heard President Obama speak for that view last week, when he basically said that if the Court decides the case “correctly” it will uphold the law.

Then we have four Justices (you know who they are) who will seriously question whether the commerce clause really is broad enough to encompass the health care law. I cannot predict that they will all vote to strike it down as exceeding that power. But their approach to answering the legal question will be totally different from the other faction. They will cite Madison, the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, John Marshall, and John Jay in trying to answer the question. It is quite likely that under such an analysis it will be difficult to uphold the law because there is no precedent for this type of requirement (mandating the purchase of insurance). These Justices will struggle with the case.

If I were to decide the case as a lay lawyer, I would side with Judge Jeffrey Sutton of the Sixth Circuit who reluctantly voted to uphold the law because he couldn’t discern from the Supreme Court precedents, which he is bound to follow, which side had the better of the argument. So he threw up his hands and kicked it up to the Supreme Court.

But the Supreme Court is not bound to follow its own precedents. Some of its cases say it is, but at least one precedent gets overturned every term, and sometimes it is more like three. So Justices with a strong view of what any constitutional provision means can engraft their opinions into law if they can persuade four of their colleagues to go along. I can hear in my mind’s ear the dialogue between Justice Scalia trying to persuade the flexible Justice Kennedy of the rightness of his view. And I can also hear the rather rigid Justice Kagan (we learned a great deal from her opinion on campaign finance two months ago) trying to persuade him of the correctness of her diametrically opposite view. But, remember, neither Scalia nor Kagan can objectively prove he or she is right. They both have much to cite, though all of Kagan's material is post-1937.

If Justice Kennedy had a way to decide such questions that he could apply in case after case, he might fairly be characterized as a “thoughtful” jurist. But he does not lay down any neutral principles for deciding constitutional cases. Rather, he agrees with one faction in one case, and the other faction in another case. The media refers to this form of adjudication as moderation. It’s more accurately described as unprincipled.

There is no moderate way to interpret anything. One can only interpret by the application of neutral principle, i.e., original meaning, plain meaning, application of precedent, textualism, etc. If the meaning of a phrase is so elusive that the judge is willing to split the baby, or flip a coin, then that judge is not acting as a judge but rather a politician.

We would be better served without moderate Justices. We should expect our presidents to appoint people to the Supreme Court who have records and judicial philosophies. By and large, this is what we are getting, though it was different when timid Republicans were in office. A jurist like Anthony Kennedy, who was President Reagan’s third choice to the Court in 1987, would not be nominated today by any president unless he, like Reagan, was desperate for someone easily confirmable. So the next election is crucial for the future of the Supreme Court and for the country since it decides so many issues like whether the healthcare law is constitutional.

I’d like to know more about Mitt Romney and Rick Perry’s judicial appointments as governors. I know what Republican presidential candidates say they are looking for in a Supreme Court justice (interpretation not legislating), which means almost nothing. They all do both when it suits them. We should demand to know more about how these candidates have appointed judges, and how equally importantly, those judges have turned out in their performance. If we see timid appointments of moderates, then we will know all we need to know.