Obamacare: One Year Later

Wednesday marked the first anniversary of the Democrats' health reform bill. But in this past year little progress has been made on addressing the real health care crisis: high costs.

Writing in The New Republic, Jonathan Cohn looked back on the past year of health reform debates. Cohn wrote:

The goal of reform was really two-fold: In the short term, to make sure everybody can afford to pay for medical bills without financial distress; it the long term, to make the health care system as a whole more efficient, so that it no longer applied such a crushing financial burden on society. A single-payer system, like the ones in France or Taiwan, would have accomplished this. So would a scheme that turned health insurance into a regulated utility, as the Dutch and Swiss governments have done.

There’s no question that if the government subsidizes healthcare payments, in part by mandating (taxing?) all of us to pay for health insurance coverage, everyone would be able to afford care without “financial distress” (whatever that means). But is the long term goal, removing the "crushing financial burden on society," achievable?

Cohn argues that adopting the Dutch, Swiss, French, or Taiwanese systems would do the trick. But 50% of U.S. healthcare spending occurs in a single payer system called Medicare (and let’s not forget Medicaid and the VA). What prevents Medicare from controlling costs?

A little noted report by the Congressional Research Service in 2007 (remember when Nancy Pelosi ran Congress?) asked the question of why U.S. healthcare spending was so much greater than for any other country in the Organization for Economic Development.

Let’s look at the myths the report shattered:

1.) Myth: It’s all about the cost of insurance and overhead: Yes, Americans spend seven times the OECD median for insurance and overhead, but this amounts to $465 dollars per capita. The difference between total spending per capita in the U.S. and the OECD median is about $4000. Moreover, OECD citizens spend a greater amount out of pocket for healthcare than Americans do (The U.S. has the 5th lowest % of out of pocket costs of the 26 nations in the OECD). The point here is that eliminating the extra 399$ per year of insurance and overhead costs would still leave the U.S. at double the cost of care in the average OECD country.

2.) Myth: It’s all about an inefficient U.S. system: I am not sure how Mr. Cohn decided the system was inefficient or what data he used but here is what the Congressional Research Service found:

The United States has fewer hospital admissions and doctor visits) than the average OECD country. The United States has a below-average number of hospital beds and practicing physicians per population but its number of nurses per population is roughly the same as the OECD average. The United States has a higher than average number of staff per hospital bed and nurses per bed. The length of hospital stays in the United States are the same as the OECD average.

With short lengths of stay, limited hospital beds and physicians and fewer admissions than the average, it's pretty hard to argue inefficiency, at least from an economic perspective. Also, the congressional study found that wait times were low in the U.S. They noted: “in a recent survey, a quarter to a third of respondents in Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia reported waiting more than four months for a non-emergency procedure, compared with only 5% of Americans.”

3.) Myth: U.S. health outcomes are terrible: Typically, critics point to high mortality rates for infants in the U.S. and below average life expectancy. Those are the data. But as the congressional researchers pointed out, “such measures are often subjective or limited by differing measurement methodologies. They may also reflect fundamental population differences (in underlying health, for example) rather than differences in countries’ health care systems.” (A good example is the fact that many countries do not count premature babies who do not survive, as live births, thereby improving their statistics.)

On the other hand, the researchers also found that “The United States has the third-highest percentage of the population that reports their health status as being 'good,' 'very good,' or 'excellent'”. Moreover, they found that “a six-country study (the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Germany) found that Americans were most likely to report receiving specific recommended preventive services for diabetic and hypertensive patients.”

This is probably the most important reason that most Americans cannot understand the benefits of Obamacare and most continue to oppose it- they're already satisfied with their care.

So what's the problem underlying the fact that the U.S. spends more than twice as much as any OECD country on healthcare? It's the price of care. The congressional research pointed out that:

Although OECD data does not compare prices of medical care, other studies have found that the United States pays higher prices for medical care than countries such as Canada and Germany. Part of the reason for this may be that U.S. general practitioners and nurses are the highest paid in the OECD, and U.S. specialists are the third-highest paid in the OECD . Health professionals in wealthier countries earn higher salaries than those in poorer countries, but even accounting for this, U.S. health professionals are paid significantly more than the U.S. GDP would predict (for example, specialists are paid approximately $50,000 more than would be expected).

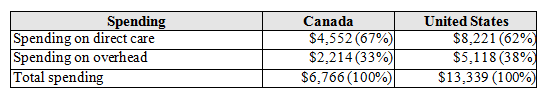

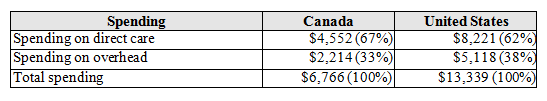

And it is not only physician costs, but also hospital costs. For example, here is a comparison of the costs of a hip replacement in the U.S. v. Canada:

It's pretty clear the only way to control health care costs is to control the price of care. Hospital utilization is low, while insurance and overhead costs are only a small component of costs in the U.S. Unless hospitals and physicians are paid a lot less, health costs will continue to be much higher here than elsewhere in the world.

Worse yet, the 5-7% per year growth in health care costs in the U.S. is the same in the rest of the OEC, mostly due to population ageing. Adopting full government control, as in most of the OECD countries, just won’t slow the rate of growth.

Since the government pays for 50% of U.S. healthcare, one could make the legitimate argument that government-insured healthcare is the driver of the costs of healthcare. Congress has been completely unable to control the price of Medicare services.

The “doc fix” is the perfect example of this failure. At this point, Medicare payments to physicians are supposed to be 30% lower than the current fee schedule. Congress has been completely impotent.

It’s hard to see how a bigger government role will fix healthcare’s cost problem. But will this administration ever let market forces help fix the problem?

Tweet