Losing the Fight Against Child Poverty

Last week, the Urban Institute released a new survey of child poverty numbers:

Usually such surveys count the number of children in poverty and find that somewhere between one child in five and one child in seven is poor in the United States. Nothing to brag about, but at least we can tell ourselves that four children out of five are NOT poor.

The Urban Institute wants us to think about child poverty in a different way.

They propose we look at child poverty not as a snapshot in time, but as a sequence over time. If we do, we'll see that more American children experience poverty than we might suppose - and that their odds of escape over time are much lower than we might hope.

* More than 1 out of 3 American children will be poor at some point in their childhood.

* You might imagine this experience as a brief or temporary one: the child on food stamps as his mother seeks work after a divorce for example. In fact, even children who experience poverty only temporarily tend to experience it recurringly: they cycle in and out of poverty, bad years following good.

* Children born into poverty are much more likely to remain poor in adulthood than children who are not born into poverty.

* Race predicts poverty: black children are 2.5x more likely to experience poverty than white, 7x more likely to be persistently poor.

The Urban Institute's numbers are based on data from 1968 to 2005. We can assume that things have taken a nasty lurch downward since 2007.

This news might seem "dog bites man."

Yes, there's a lot of poverty in America, yes it's hard to escape, yes minorities are more likely to be poor than whites ... tell me something I don't know.

But even if it's a familiar story, it bears thinking anew for this reason:

America suffers much more child poverty than do comparably wealthy countries - Germany, France, Canada, etc. - for two main reasons:

* Our much higher levels of immigration and especially unskilled immigration, which continually add to the population of poor in this country.

* Our much lower levels of social spending, which mean that poor families receive far less social support than do poor families in other countries.

Many Americans see these two differences between the U.S. and other rich countries as evidence - or at least as a price worth paying - for America's superior economic dynamism and social mobility.

As Rich Lowry and Ramesh Ponnuru wrote in an important statement for National Review about the superiority of the U.S. over the European model:

American attitudes toward wealth and its creation stand out within the developed world. Our income gap is greater than that in European countries, but not because our poor are worse off. In fact, they are better off than, say, the bottom 10 percent of Britons. It’s just that our rich are phenomenally wealthy.

This is a source of political tension, but not as much as foreign observers might expect, thanks partly to a typically American attitude. A 2003 Gallup survey found that 31 percent of Americans expect to get rich, including 51 percent of young people and more than 20 percent of Americans making less than $30,000 a year. This isn’t just cockeyed optimism. America remains a fluid society, with more than half of people in the bottom quintile pulling themselves out of it within a decade.

But what if it turns out that America is not really such a fluid society?

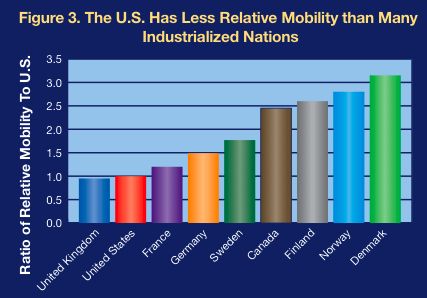

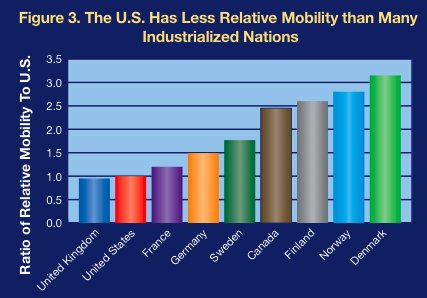

I've referred before to this Brookings Institution study, published in 2009.

Pay special attention to this chart from page 5.

Only the UK does worse than the US among the 9 countries surveyed - and the social democratic countries of Scandinavia all do better.

This is not an argument in favor of the European way of doing things. I agree with Lowry and Ponnuru - and Charles Murray too - that American freedom and individualism are important national values to be celebrated and defended.

But let's not flatter ourselves: Those values exact a social cost - and they would be easier to defend if the cost were less high. And the fact that this cost is not being paid by my children or (probably) yours does not make the cost less real to the one-third of America whose children do pay it.