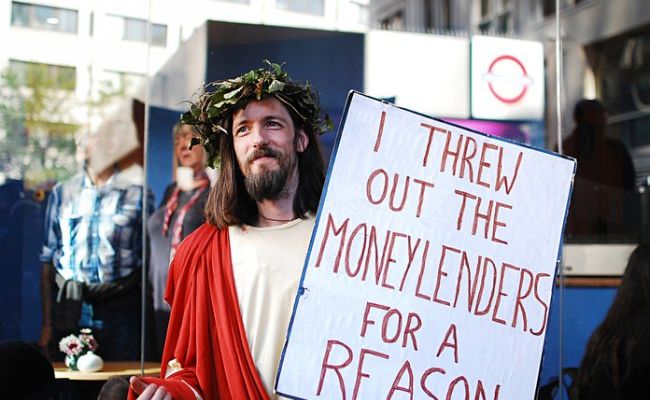

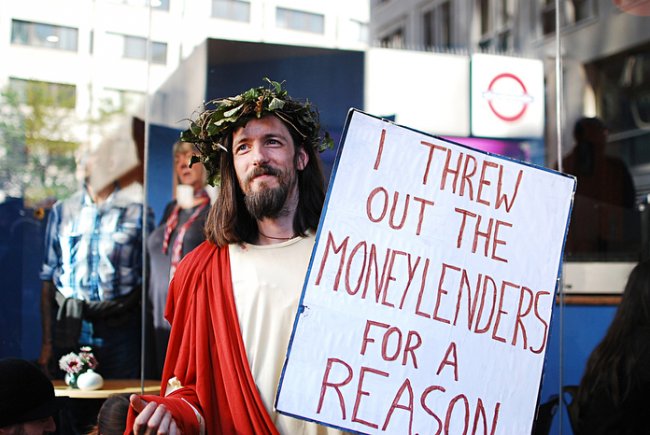

Is This What Democracy Looks Like?

Anne Applebaum has just written the best column I've yet seen on the Occupy Wall Street protests. She makes two key points, one chastening to OWS supporters, one to skeptics.

Counter supporters, Anne notes:

[T]hese international protests do have a few things in common, both with one another and with the anti-globalization movement that preceded them. They are similar in their lack of focus, in their inchoate nature, and above all in their refusal to engage with existing democratic institutions. In New York, marchers chanted, “This is what democracy looks like,” but actually, this isn’t what democracy looks like. This is what freedom of speech looks like. Democracy looks a lot more boring. Democracy requires institutions, elections, political parties, rules, laws, a judiciary and many unglamorous, time-consuming activities.

But counter skeptics, Anne points out that the protests - especially in Europe - are sounding a note of protest against the insufficiency of existing national democratic institutions in a trans-national world.

Nobody much admires powerless leaders. Nobody much sees the point in voting for people who can’t stop another wave of economic pain rolling in from Beijing, Brussels or New York. If you’re upset about the austerity program being imposed on your country by indebted banks on the other side of the world, it doesn’t seem logical to complain to the mayor of Seville.

The emergence of an international protest movement without a coherent program is therefore not an accident: It reflects a deeper crisis, one without an obvious solution. Democracy is based on the rule of law. Democracy works only within distinct borders and among people who feel themselves to be part of the same nation. A “global community” cannot be a national democracy. And a national democracy cannot command the allegiance of a billion-dollar global hedge fund, with its headquarters in a tax haven and its employees scattered around the world.

This latter point applies with extra force to the protests within the EU, which seem directed as much against local austerity programs as against international banks.

The emerging response to the Eurozone debt crisis looks more and more like the response Alexander Hamilton proposed to the debt problems of the early United States: have a higher governmental authority with superior credit assume responsibility for the unsupportable debts of lower authorities with compromised credit.

To succeed, such a scheme requires two elements in the higher authority, both lacking in today's EU: taxing power (to service the debt) and political legitimacy (to justify the taxing power). The solutions in Europe are imposed from who-knows-where. The protesters have only a local return-address to which to deliver their discontents. That is precisely what democracy does not look like.