Education Reform Starts Locally

Education is local. Throughout the history of the United States, this has always been true. Local education has resulted in one of the strongest economies of all time, in a country that produces more patents than any other nation, and boasts six of the top ten universities in the world according to em>U.S. News<. Despite the myriad horror stories chronicling the sorry state of affairs students and teachers face in overstuffed classrooms across the country, by and large America's schools are not failing. In fact, quite the contrary is true. And while we have much to learn from the success stories of other nations such as Finland and Denmark, we should avoid drastic measures in favor of smaller, more localized reform. What works for Finland may not work for Tennessee. Indeed, what works for New York may not work for Tennessee.

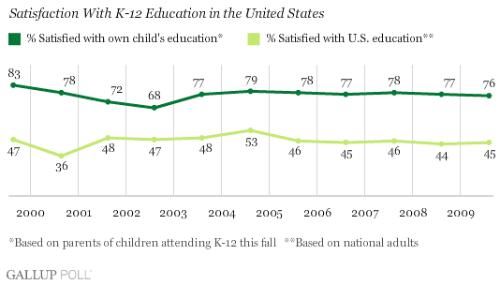

Seven years after the enactment of No Child Left Behind (NCLB), only 21% of Americans believe the program has made our education system any better, whereas 45% believe that NCLB hasn't made much difference one way or another and 29% believe it's made things worse. Most Americans without children don't have any firsthand experience with our current education system, and while American parents are by and large perfectly content with their kids' schools, parents and non-parents alike worry that education itself is in need of serious overhaul. In fact, American parents rate their own child's education at 76% favorable, while paradoxically rating the U.S. education system as a whole at only 45%.

Apparently this irony is nothing new:

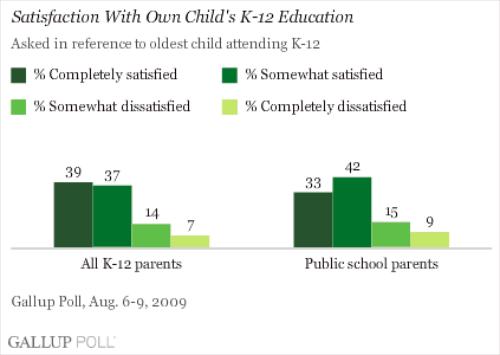

According to Gallup, parents of children in private school are 76% likely to be either completely or somewhat satisfied with their children's education, while parents of public school kids score only one point lower at 75%.

At first blush, this seems to indicate that American schools are not, in fact, in as sorry a state as is so often reported. Indeed, while there is no universal metric by which to measure the quality of America's schools (though many organizations do try), the testimony of parents is perhaps the best.

So why the constant uproar over the state of our nation's schools if parents are mostly satisfied? Why the incessant calls from groups on both the right and the left to do something? And why does anyone believe that the federal government is the proper entity to take on education reform? Certainly in matters such as healthcare, the nature of interstate trade and regulation makes federal involvement all but necessary.

Education, however, is another matter altogether.

Education is local.

This doesn't mean that educators and administrators across the country shouldn't work together to increase outcomes for their students. With advancements in information and communication technology and an increasingly vibrant open source movement, educators have access to more information than ever before, and at a fraction of the cost. Schools should find ways to work together to boost opportunities for their students and to explore innovative teaching and learning techniques. Open-source or collaborative curriculum has the potential to cut costs and to put innovative thinkers and educators together skipping the layers upon layers of bureaucracy altogether. Powerful unions and outdated tenure laws should be reviewed and reformed, especially where unions hold far too much sway.

The surest way to kill the next wave of innovation is to allow the federal government to become even more involved than it already is. If anything, No Child Left Behind should serve as a cautionary tale, not as the first step in nationalizing America's schools.

The fact is many in the media and among activist groups blow the problems with our education system out of proportion, overwhelming the public with stories of failure and injustice. Between frightening television dramas, and even more frightening news reports, it’s no wonder Americans fear for our schools. This creates the disconnect we see in how parents rate their own schools compared to how they rate education overall.

There is some truth to these stories, of course, which is why they are so potent. Many inner city schools really do suffer from all the things we hear about - gang violence, illiteracy, poverty, and incompetent teachers and administrators. In many areas, teachers unions have far too much power, and tenure and seniority laws make firing bad teachers nearly impossible, retaining even the most incompetent, or placing suspended teachers on indefinite leave with pay.

But people confuse these isolated truths with the bigger picture, and imagine that only sweeping, national reform will lead to change. When reform is called for on national platforms people forget that education is local - and that the only true and lasting reforms will be local too.

This is not to say that these truly under-performing districts don't need help from the outside. Often these schools are located in impoverished areas; teachers are overwhelmed and underpaid; local and school officials are corrupt or ineffective. Union leaders hold far too much sway, and bad teachers are too difficult to fire - while good teachers are nearly impossible to retain. In these really bad scenarios, outside involvement can tip the balance. Federal intervention has its place, so long as it is limited and focused. Vouchers, pay for performance, charter schools, and union reform all have their place, though problems, and thus solutions, vary widely from one city to the next.

Whereas vouchers may work in some of these neighborhoods, they are anything but a panacea when it comes to education reform. Vouchers and, more broadly, school choice can be important steps to breaking up bad school districts, but they won’t work everywhere – especially where teachers unions don’t have as much power.

Carrots and sticks are also sometimes necessary. D.C. School Chancellor Michelle Rhee has introduced a two-track program, attempting to lure teachers outside of the protections of tenure with higher pay and a stronger emphasis on performance. Education Secretary Arne Duncan wants to use stimulus money to fund states that “expand school days, reward good teachers, fire bad ones and measure how students perform compared with peers in India and China.”

Implemented properly, these sorts of reforms might work – pressuring states to break up powerful unions and begin experimenting with new ideas, adopting new pay-for-performance programs and setting up charters. So long as the federal government doesn’t insist on which reforms states need to adopt but focuses rather on the results of those reforms, there could be some merit to Duncan’s proposals.

Federal funds should not come with layer upon layer of red tape and thousands of strings attached. If federal funds are distributed, schools should be allowed to allocate them as they see fit once they’ve shown that they are willing to take on essential reforms. And hopelessly corrupt and under-performing schools should face federal intervention, not receive a government check. Nor should federal money be used to merely shore up state budgets, but rather as a focused system of rewards and assistance for states or even localities which implement reform.

Most American parents are happy with their schools, and this has been true for decades. The public school system is one of the best expressions of local government (and indeed government of any scale), and represents an opportunity for communities and their youth to come together not only to learn but to express what those communities stand for and believe in. The federal government can never replicate the success that we've had as a nation locally no matter how brilliant the education wonks they hire are, or how clever their standardized test writers may be. We simply can't rely on central planners to manage education. They're too disconnected from the trenches, and too bound by their own clever ideas to respond to the realities on the ground.

Education is local, and it should remain that way. There are many good ideas out there for our schools, and we should do our best to try these ideas out all across the country, publish their results, and work together to find solutions that fit each community. Charters, magnets, and pay-for-performance are all ideas that seem to be gaining traction with great success. Let's keep big government and big labor out of our schools as much as possible, give teachers back their autonomy and accountability, and let communities, educators, and parents be the driving force behind education reform.

In the end, I'm sure we'll be about 70 to 80% satisfied with the results.