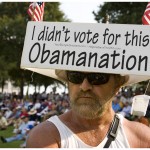

Media to Tea Partiers: Can You be More Racist?

Many in the media have accused the tea party protests of being motivated by racism. The most troubling critiques though actually seem to fault the tea partiers for not discussing race enough.

Many in the media have accused the tea party protests of being motivated by racism. The most troubling critiques though actually seem to fault the tea partiers for not discussing race enough.

You don't have to be a Tea Partier yourself (which I emphatically am not) to be disturbed by the critiques of the Tea Party movement. In The New York Times, for example, Charles Blow decries Tea Parties as a "political minstrel show" that misleadingly showcases their few non-white supporters. In The New Republic, Jonathan Chait concedes that the Tea Parties are "not racist" but warns that “the ideology of the movement is difficult to separate from views about race” and that it “fits in snugly with a racialized vision of government.” Minstrel shows, racialized visions of government, crowds of white people with "views about race": Sounds ominous!

Actually, it’s not. Chait and Blow insinuate a far worse depiction of Tea Partiers than the one they actually draw. Indeed, to the extent that Chait and Blow have any genuine objection to Tea Parties, it is that they exhibit too much naive goodwill and desire to do what's right for the country as a whole.

Start with Chait's claim that Tea Party ideology "fits in snugly with a racialized vision of government." This is true and sinister-sounding but also vacuous. Yes, one may support Tea Party policies for racist reasons ("No more spending our hard-earned taxpayer dollars to help black people!"). By the same token, one may support liberal policies for fascist reasons ("The will of the Volk demands that the health care system be nationalized!"). Chait himself thinks it's hilarious when right-wingers try to tar liberals as fascists based on coincidental ideological overlaps. Yet Chait makes the same mistake when attacking an ideology he doesn't like. Tea Partiers are no more racist because racists may support their programs than liberals are fascist because fascists may support their programs. Both are fallacious arguments ad hominem.

More subtle is Chait's claim that Tea Partiers' views are "difficult to separate" from views about race. But what American political ideology can be separated from views about race? Race issues in America are virtually impossible to avoid, for the simple reason that whites and blacks (and others, especially in the past 40 years) have lived together in this country since the very beginning, and not always -- to put it mildly -- harmoniously. Modern progressivism, for example, holds that (i) America has a history of discrimination against minorities, (ii) that history accounts for the relative lack of achievement of many minority groups, and, therefore, (iii) the government should actively redress past discrimination. These are nothing if not “views about race.” On issues like affirmative action, progressives even believe that government should discriminate against whites in favor of minorities. Regardless of its merits, this is a frankly "racialized vision of government."

We should expect Tea Partyism to have views about race no less than any other ideology. What offends Chait about Tea Partiers is not that they have "views about race" -- which Chait himself presumably has as well -- but that they do not make their views explicit. Officially, Tea Partiers only want the government to tax and spend less. What could fiscal policy have to do with race? Well, according to Chait, though they want to cut government, it turns out that Tea Partiers have no beef with middle class entitlements such as Social Security and Medicare. They are also more likely to oppose government efforts to help minorities. These features, Chait argues, add up to an unacknowledged fear that the government is increasingly being run to benefit racial minorities at the public's expense.

Fine. Even if Chait is right, it still doesn't mean that Tea Partiers have some nefarious hidden motives. The views on race that Tea Partiers refuse to acknowledge are utterly conventional. They consist simply of 1970s-era neoconservatism: there are "limits to social policy;" in particular, there are limits on the government's ability to achieve racial equality. Just like Tea Partiers of today, neoconservatives such as Irving Kristol had no objection to middle class entitlements, which they praised precisely because they (historically) were open to all and not means-tested. Chait wants Tea Partiers to express their subconscious fears. It turns out, however, that those fears were expressed some time ago, with impressive intellectual and political results.

Finally, Blow -- as does Chait -- observes that Tea Partiers are mostly white. Of course, so are most people who drive electric-powered cars, go on nature walks, fret about their carbon footprints, recycle religiously and shop at Whole Foods. Presumably Blow does not condemn these activities, or the ideologies that rationalize them, merely because of their overwhelming whiteness. On the contrary, what apparently upsets Blow is that Tea Partiers take pains to show that their movement is not exclusively white. In other words, Tea Partiers want their ideas to be embraced by Americans of all colors. One would think that this is the very thing that Blow should be happy about that.

But he is not. He thinks the Tea Partiers are hypocrites "engaged in the subterfuge of intolerance": they say that they only want what's best for America, but if you look only a little deeper, it turns out that they are driven by white racial anxiety. Even if that's true, Tea Partiers are still sublimating their racial anxieties and making appeals solely to the public good. Those appeals can then be judged on their merits, without reference to the skin color of the people making them. Does Blow wish instead that Tea Partiers turn themselves into a far right movement that's only interested in what's good for white people? Presumably not. It is vital to the future of this country that such a thing never happen. Yet Blow's op-ed amounts to the complaint that it is not happening. He wants Tea Partiers to be more forthrightly racist and therefore less hypocritical, or else shut up and be content to be politically voiceless. If any political stance today is troubling, it is this one.