Courts Must Say Who is a Security Risk

In the bad old days of the Cold War, when Soviet espionage and subversion was rampant, it was a given that in questions of security versus individual rights, preference was given to the state.

In other words, in sensitive areas of national security, if suspicions of treason or of being co-opted by the KGB, couldn’t be proven definitively, the verdict rendered was usually to protect the state. It’s pretty hard to argue with that.

It doesn’t mean that the individual in question is punished or convicted, but it does mean that the person remains a security “risk,” albeit not a security “breach.”

The old Cold War guidelines don’t apply so much any more – and in fact were never very effective at curbing Soviet penetration of Canadian institutions such as the CBC, which always showed more concern about the possibility of CIA activities in Canada than KGB penetration.

At one point, the KGB managed to infiltrate a senior officer (Rudi Hermann) as a CBC soundman. The guy was eventually exposed in the U.S.

That was then, this is now.

With KGB subversion and Soviet expansion no longer a threat, another menace has emerged – international and domestic terrorism.

Right now, two guys with questionable records are suing the Canadian government (for over $20 million each) for allegedly abusing their rights. The usual civil liberties activists seem to be siding with them.

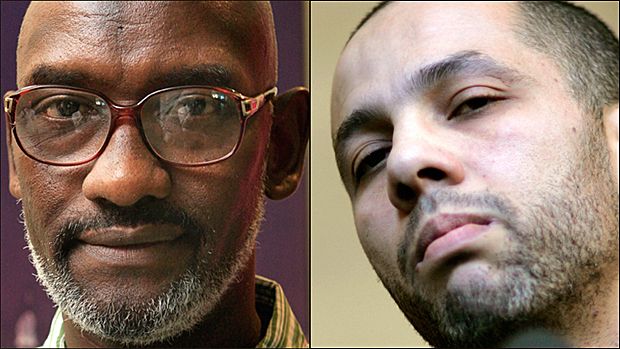

The two are Adil Charkaoui, a Moroccan whom CSIS apparently suspects was an al-Qaida sleeper agent, and Abousfian Abdelrazik, a Canadian who is on a UN no-fly list of al-Qaida types, and who was being held in Sudan until the federal court in 2009 ruled he should be returned to Canada.

The Canadian government (through Immigration Minister Jason Kenney) is outraged to the point of apoplexy over the case.

Leaked transcripts to La Presse in Quebec purport to be an encrypted conversation between the two men in 2000, discussing plans to blow up an Air France passenger plane.

The individuals say it’s a smear, and their lawyer (rightly) feels that the leaked the transcript is an attempt (by the UN bureaucracy) to undermine the case against the two guys.

Details remain vague. Immigration Minister Kenney insists that while he can’t discuss security matters, he does acknowledge that Canada’s actions are not based on mere “hunch ... not based on innuendo ... not based on speculation ... (but) are based on very robust intelligence.”

For most of us, that assurance should end the argument. Whatever the truth is, in security matters one has to side with the state.

According to La Presse, the leaked documents indicate that traces of RDX (an ingredient of high-tech explosives) were found in Mr. Abdelrazik’s car.

Adding to the mystery is that in the past, CSIS withdrew its case against Mr. Charkaoui because it did not want to use evidence it considered too sensitive to become public knowledge.

If this is true (and one assumes it is), it is still national security interests versus individual rights. Again, protection against possible terrorism takes precedence.

At the moment these guys are not facing jail, but they and their lawyers evidently feel the Crown is in retreat, and therefore vulnerable to a law suit. Money is now the goal.

The way the justice system works, they may well get a pay day. One hopes not, but stranger things have happened.