Christmas in Europe, 1944

Belgium, sixty five years ago:

httpvh://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y7bbJ4fzOCE

The Battle of the Bulge was the single largest and bloodiest battle American forces experienced in World War II.

In all, 840,000+ Allied soldiers participated in the Battle, with 1,300 medium tanks, plus tank destroyers, and 394 artillery pieces.

19,246 Americans were killed in the Bulge, 47,500 wounded, 23,000 captured or missing (an astonishing 89,746 total casualties), approximately 800 tanks destroyed. 200 British soldiers were killed, 1,200 wounded or missing.

They fought and died for our freedom. Remember them as you enjoy your Christmas festivities this year, and every year.

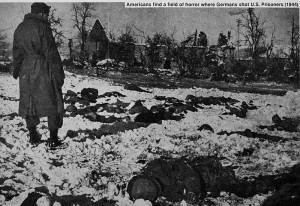

Due to horrific conditions at the hands of the Wermacht, many of these GI's did not survive their captivity

Due to horrific conditions at the hands of the Wermacht, many of these GI's did not survive their captivity

The German Wehrmacht went into the offensive with 500,000 men, 1,800 tanks, and 1,900 artillery pieces. 67,200 German Wehrmacht were killed, 32,800 wounded or missing and approximately 700 tanks destroyed. On top of these staggering statistics, approximately 3000 civilians were killed during the course of the Ardennes campaign of 1944-45.

I have lived in and around the Fort Bragg area for many years. There are not too many WWII paratrooper veterans left, but I have had the honor to meet a few over the years. I knew a retired Sergeant Major who served with the 101st in Normandy, the Low Countries and was at Bastogne. I asked him once, "How did you do it? How on Earth did paratroopers fight tanks, and hold out?"

"Oh, well, we just did what we had to do to stay alive."

"I always heard they put you guys in there without any winter gear?"

"All we had was bedsheets, white bedsheets, over our uniforms."

"Oh man. How did you do it? How did you deal with the cold?"

"Oh my Lord, that was the coldest I have ever been in my entire life. I will never forget that cold, as long as I live. On Christmas Day, they served turkey stew. We were on the front lines, we'd have to go back one at a time. They'd fill our canteen cups with turkey stew, and by the time we'd get back to our positions, the turkey stew would be frozen solid."

Kind of puts the great Blizzard of 2009 into perspective, doesn't it?

* * *

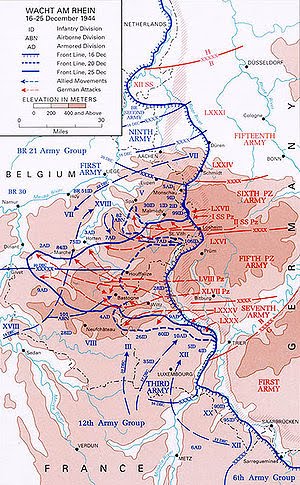

A massive artillery barrage in the early morning hours of 16 December 1944 signaled the beginning of a massive German assault on Allied positions in the Ardennes forest.

By 0800 hours three German armies attacked through the Ardennes. Waffen SS General Sepp Dietrich’s Sixth SS Panzer Army moved toward the offensive’s primary objective: Antwerp, to capture the critical Allied supply depots there – most especially the fuel dumps. In the center von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army attacked toward the strategic road junction cities of Bastogne and St. Vith.

To the north at Lanzerath, Belgium and the Elsenborn Ridge, attacks by the Sixth SS Panzer Army’s infantry units encountered unexpectedly fierce resistance by the U.S. 2nd and 99th Infantry Divisions. On the first day, an entire German battalion was held up for 20 hours by a single 18-man Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon from the 99th Infantry Division, causing a bottleneck in the German advance.

As it became obvious to the Allied High Command that the German attacks represented a major Nazi offensive, snowstorms engulfed the Ardennes. While having the desired effect of keeping the Allied aircraft grounded, the weather also proved troublesome for the Germans because poor road conditions hampered their advance. Poor traffic control led to massive traffic jams and fuel shortages in forward units.

[/caption]

[/caption]

Malmedy Massacre

The main armored spearhead of the Sixth SS Panzer Army was Kampfgruppe Peiper; 4,800 men and 600 vehicles of the 1st SS Panzer Division under the command of Waffen-SS Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Joachim Peiper. At 07:00 on 17 December, they seized a U.S. fuel depot at Büllingen, where they paused to refuel before continuing westward.

At 12:30, near the hamlet of Baugnez, on the height halfway between the town of Malmedy and Ligneuville, forward elements of Kampfgruppe Peiper captured troops of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, U.S. 7th Armored Division. The Americans were disarmed and sent to stand in a field near the crossroads, where approximately 150 of them were machinegunned to death.

Even though executing prisoners and shooting civilians were a trademark of Waffen SS operations, news of the killings raced through Allied lines. Although there is no record of an SS officer giving an execution order, following the war SS soldiers of Kampfgruppe Peiper were to be held accountable during the Malmedy massacre trial.

Belgian civilians killed by SS units during the offensive

Belgian civilians killed by SS units during the offensiveThe fighting went on. By the evening of the 16th Peiper was already behind schedule; it had taken him 36 hours to advance from Eifel to Stavelot, compared to just 9 hours in 1940. As the Americans fell back, they blew up bridges and fuel dumps, denying the Germans critically needed fuel and further slowing their progress.

In the central 'Schnee Eifel' sector, the Fifth Panzer Army surrounded two regiments (422nd and 423rd) of the 106th Division in a pincer movement and forced their surrender. The official U.S. Army history states: "At least seven thousand men were lost here (the figure was probably closer to eight or nine thousand). This substantial amount of manpower, arms and equipment represents the most serious reverse suffered by American arms during the operations of 1944–45 in the European theater."

American soldiers taken prisoner by the German Wehrmacht

American soldiers taken prisoner by the German WehrmachtFurther south the main German thrust crossed the River Our, increasing pressure on the key road centers of St. Vith and Bastogne. The 112th Infantry Regiment (of the US 28th Division), held a continuous front east of the Our, keeping German forces from seizing and using the Our river bridges around Ouren for two days before withdrawing progressively to the west.

The 109th and 110th Regiments both offered stubborn resistance in the face of superior forces, keeping the German offensive days off schedule. Denied their intended avenues of approach, Panzer columns took outlying villages and widely separated strong-points in bitter fighting, slowed in their advance to Bastogne.

An American road-block with .30 caliber machine gun in the Ardennes, December 1944

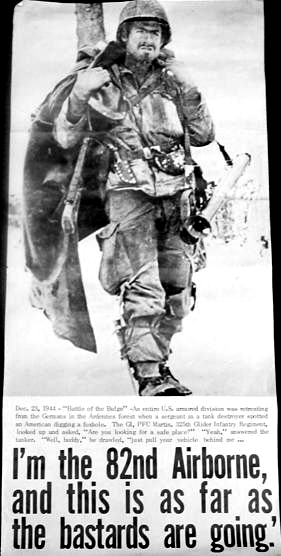

An American road-block with .30 caliber machine gun in the Ardennes, December 1944By 17 December, Eisenhower and his principal commanders realized that the fighting in the Ardennes was a major offensive and not a local counter-attack, and they ordered vast reinforcements to the area. Within a week 250,000 troops had been sent. In addition, the 82nd Airborne Division was also thrown into the battle north of the bulge, near Elsenborn Ridge.

St. Vith

In the center of the 'Bulge' salient the town of St. Vith, a vital road junction, presented a major challenge for German Wehrmacht forces. The defenders included the 7th U.S. Armored Division, and remnants of the 106th U.S. Infantry, with elements of the 9th U.S. Armored and U.S. 28th Infantry, all under the command of General Bruce C. Clarke.

Clarke's forces successfully resisted the German attacks, significantly slowing their advance. Under orders from Montgomery, St. Vith was given up on 21 December; U.S. troops fell back to entrenched positions in the area, presenting an imposing obstacle to a successful German advance. By 23 December, as the Germans shattered their flanks, the defenders’ position became untenable, and U.S. troops were ordered to retreat west of the Salm River. As the German plan had originally called for the capture of St. Vith by 18:00 on 17 December, the prolonged action in and around the city presented a major blow to their timetable.

U.S. M4 Sherman tanks take up positions on the outskirts of St. Vith, 20 December 1944

U.S. M4 Sherman tanks take up positions on the outskirts of St. Vith, 20 December 1944The struggle for the villages and American strong-points, plus transport confusion on the German side, slowed the attack sufficiently to allow the 101st Airborne Division (reinforced by elements from the 9th and 10th Armored Divisions) to reach Bastogne by truck on the morning of 19 December. In fierce defensive fighting, the American paratroopers denied the Germans their critical objective Bastogne, with its important road junctions. Panzer columns swung past on either side, cutting off Bastogne on 20 December but failing to secure the vital crossroads.

Bastogne

According to Wehrmacht plan, by 19 December the town of Bastogne and its network of eleven hard topped roads leading through the mountainous terrain and boggy mud of the Ardennes region were to have been in German hands for several days.

Eisenhower realized the Allies could destroy German forces much more easily when they were out in the open and on the offensive than if they were on the defensive. Meeting with senior Allied commanders in a bunker in Verdun, Ike told his generals, "The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster. There will be only cheerful faces at this table."

General Dwight Eisenhower poses with a group of soldiers during a visit to the Battle of the Bulge battlefield. The soldiers were members of the 334th Anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA) Battalion

General Dwight Eisenhower poses with a group of soldiers during a visit to the Battle of the Bulge battlefield. The soldiers were members of the 334th Anti-Aircraft Artillery (AAA) BattalionBy the time of that meeting, two separate west-bound German columns were to have by-passed Bastogne to the south and north, the 2nd Panzer Division and Panzer-Lehr-Division of XLVII Panzer Corps, as well as the 26th Volksgrenadier Division. Instead these units had been engaged and slowed in frustrating battles at outlying defensive positions up to ten miles from the town proper.

Members of the 101st Airborne Division armed with bazookas, on guard for enemy tanks. On the road leading to Bastogne, Belgium, 23 December 1944

Members of the 101st Airborne Division armed with bazookas, on guard for enemy tanks. On the road leading to Bastogne, Belgium, 23 December 1944Eisenhower asked Patton how long it would take to turn his Third Army (located in northeastern France) north to counterattack. To the disbelief of the other generals present, Patton said he could attack with two divisions within 48 hours. Before he had gone to the meeting, Patton had already ordered his staff to prepare three contingency plans for a northward turn in at least corps strength. By the time Eisenhower asked him how long it would take, the movement was already underway. On 20 December, Eisenhower removed the First and Ninth U.S. Armies from Bradley’s 12th Army Group and placed them under Montgomery’s 21st Army Group.

By 21 December, the German forces had Bastogne surrounded. Conditions inside the Bastonge perimeter were tough — most medical supplies and medical personnel had been captured, food was scarce, and by December 22 artillery ammunition was restricted to 10 rounds per gun per day. The weather cleared the next day, however, and supplies (primarily ammunition) were dropped in by parachute over four of the next five days.

The perimeter held despite determined German attacks. The German commander, Generalleutnant Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz, requested Bastogne's surrender. When acting commander of the 101st General Anthony McAuliffe was told of this, he responded with a frustrated, "Aw, nuts!" After turning to other pressing issues, his staff reminded him that they should reply to the German demand. One officer (Lt. Col Harry W. O. Kinnard) recommended that McAuliffe's initial reply would be "tough to beat". Thus McAuliffe wrote on the paper delivered to the Germans: "NUTS!" The famous reply - a morale booster to his troops - had to be explained both to the Germans, and to non-American Allies.

General Patton pinning the Distinguished Service Cross on BG Anthony C. McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st Airborne Division during the Siege of Bastogne

General Patton pinning the Distinguished Service Cross on BG Anthony C. McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st Airborne Division during the Siege of BastogneBoth 2nd Panzer and Panzer Lehr moved forward from Bastogne after December 21, leaving only Panzer Lehr's 901st Regiment to assist the 26th Volksgrenadier Division in attempting to capture the crossroads. The 26th VG received one panzergrenadier regiment from the 15th PzG Division on Christmas Eve for its main assault the next day. Because it lacked sufficient troops and those of the 26th VG Division were near exhaustion, the XLVII Panzer Corps concentrated its assault on several individual locations on the west side of perimeter in sequence rather than launching one simultaneous attack on all sides. The assault, despite initial success by its tanks in penetrating the American line, was defeated and all the tanks destroyed. The next day, December 26, the spearhead of the 4th Armored Division broke through and opened a corridor to Bastogne.

In the extreme south, Brandenberger’s three infantry divisions were checked after an advance of four miles (6.5 km) by divisions of the U.S. VIII Corps; that front was then firmly held. Only the 5th Parachute Division of Brandenberger’s command was able to thrust forward 12 miles (19 km) on the inner flank to partially fulfill its assigned role.

GERMAN DECEPTION & SPECIAL OPERATIONS IN THE ARDENNES

Before the offensive, the Allies were virtually blind to German troop movement. During the reconquest of France, the extensive network of the French resistance had provided valuable intelligence about German dispositions. Once they reached the German border, this source dried up. In France, orders had been relayed within the German army using radio messages enciphered by the Enigma machine, and these could be picked up and decrypted by Allied code-breakers to give the intelligence known as ULTRA.

German Wehrmacht soldiers sending an encrypted message via the Enigma machine

German Wehrmacht soldiers sending an encrypted message via the Enigma machine The foggy autumn weather also prevented Allied reconnaissance planes from correctly assessing the ground situation

The foggy autumn weather also prevented Allied reconnaissance planes from correctly assessing the ground situationIn Germany, such orders were typically transmitted using telephone and teleprinter, and a special radio silence order was imposed on all matters concerning the upcoming offensive. The major crackdown in the Wehrmacht after the 20 July plot resulted in much tighter security and fewer leaks.

Waffen SS Obersturmbahnfuhrer Otto Skorzeny - "the Most Dangerous Man in Europe"

Waffen SS Obersturmbahnfuhrer Otto Skorzeny - "the Most Dangerous Man in Europe"Two major special operations were planned for the offensive. By October it was decided Otto Skorzeny, the German commando who had rescued the former Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, was to lead a task force of English-speaking German soldiers in Operation Greif.

These soldiers were to be dressed in American and British uniforms and wear dog tags taken from corpses and POWs. Their job was to go behind American lines and change signposts, misdirect traffic, generally cause disruption and to seize bridges across the Meuse River between Liège and Namur.

By late November another ambitious special operation was added: Colonel Friedrich August von der Heydte was to lead a Fallschirmjäger (paratrooper) Kampfgruppe in Operation Stösser, a nighttime paratroop drop behind the Allied lines aimed at capturing a vital road junction near Malmedy.

Operation Stösser

Originally planned for the early hours of 16 December, Operation Stösser was delayed for a day because of bad weather and fuel shortages. The new drop time was set for 03:00 on 17 December; their drop zone was 7 miles (11 km) north of Malmedy and their target was the "Baraque Michel" crossroads. Von der Heydte and his men were to take it and hold it for approximately twenty-four hours until being relieved by the 12th SS Panzer Division, thereby hampering the Allied flow of reinforcements and supplies into the area.

Fallschirmjäger exiting a JU 52 in the unique German headfirst technique

Fallschirmjäger exiting a JU 52 in the unique German headfirst techniqueJust after midnight on 17 December, 112 Ju 52 transport planes with around 1,300 Fallschirmjägern took off amid a powerful snowstorm, with strong winds and extensive low cloud cover. As a result, many planes went off course, and men were dropped as far as a dozen kilometers away from the intended drop zone, with only a fraction of the force landing near it. Strong winds also took off-target those paratroopers whose planes were relatively close to the intended drop zone and made their landings far rougher.

By noon, a group of around 300 managed to assemble, but this force was too small and too weak to counter the Allies. Colonel von der Heydte abandoned plans to take the crossroads and instead ordered his men to harass the Allied troops in the vicinity with guerrilla-like actions.

Wehrmacht Fallschirmjägeren in combat, 1944

Wehrmacht Fallschirmjägeren in combat, 1944Because of the extensive dispersal of the jump, with Fallschirmjägeren being reported all over the Ardennes, the Allies believed a major division-sized jump had taken place, resulting in much confusion and causing them to allocate men to secure their rear instead of sending them off to the front to face the main German thrust.

Operation Greif and Operation Währung

For Operation Greif, Otto Skorzeny successfully infiltrated a small part of his battalion of disguised, English-speaking Germans behind the Allied lines. Although they failed to take the vital bridges over the Meuse, the battalion’s presence produced confusion out of all proportion to their military activities, and rumors spread quickly. Even General Patton was alarmed and, on 17 December, described the situation to General Eisenhower as “Krauts… speaking perfect English… raising hell, cutting wires, turning road signs around, spooking whole divisions, and shoving a bulge into our defenses.”

Checkpoints were set up all over the Allied rear, greatly slowing the movement of soldiers and equipment. Military policemen drilled servicemen on things which every American was expected to know, such as the identity of Mickey Mouse’s girlfriend, baseball scores, or the capital of Illinois. This last question resulted in the brief detention of General Bradley; although he gave the correct answer — Springfield — the GI who questioned him apparently believed the capital was Chicago.

The tightened security nonetheless made things harder for the German infiltrators, and some of them were captured. Even during interrogation they continued their goal of spreading disinformation; when asked about their mission, some of them claimed they had been told to go to Paris to either kill or capture General Eisenhower. Security around the general was greatly increased, and he was confined to his headquarters.

Because these prisoners had been captured in American uniform, they were later executed by firing squad. This was the standard practice of every army at the time, although it was left ambiguous under the Geneva Convention, which merely stated soldiers had to wear uniforms that distinguished them as combatants. In addition, Skorzeny was aware under international law such an operation would be well within its boundaries as long as they were wearing their German uniforms when firing.

Skorzeny and his men were fully aware of their likely fate, and most wore their German uniforms underneath their Allied ones in case of capture. Skorzeny avoided capture, survived the war, and may have been involved with the Nazi ODESSA escape network.

Otto Skorzeny addressing his troops in the field

Otto Skorzeny addressing his troops in the fieldFor Operation Währung, a small number of German agents infiltrated Allied lines in American uniforms. These agents were then to use an existing Nazi intelligence network to attempt to bribe rail and port workers to disrupt Allied supply operations. This operation was a failure.

Eisenhower Rumor

So great was the confusion caused by Operation Greif that the U.S. Army saw spies and saboteurs everywhere. Perhaps the largest panic was created when a commando team was captured near Aywaille on 17 December. Comprising Unteroffizier Manfred Pernass, Oberfähnrich Günther Billing, and Gefreiter Wilhelm Schmidt, they were captured when they failed to give the correct password. It was Schmidt who gave credence to a rumour that Skorzeny intended to capture General Eisenhower and his staff.

A document outlining Operation Greif's elements of deception (though not its objectives) had earlier been captured by the US 106th Infantry Division near Heckhuscheid, and because Skorzeny was already well-known for rescuing Italian dictator Benito Mussolini (Operation Oak or Unternehmen Eiche) and Operation Panzerfaust, the Americans were more than willing to believe this story and Pernass, Billing, and Schmidt were given a military trial at Henri-Chapelle, sentenced to death, and executed by a firing squad on 23 December. Thirteen other men were tried and shot at either Henri-Chapelle or Huy.

More to come...

Eisenhower was reportedly unamused by having to spend Christmas 1944 isolated for security reasons

Eisenhower was reportedly unamused by having to spend Christmas 1944 isolated for security reasonsOriginally posted at STORMBRINGER.