Cameron's Unrealistic Expectations

The odds that David Cameron will be able to significantly shrink Britain's government, after making concessions to voters and a left-wing party, are slim.

The odds that David Cameron will be able to significantly shrink Britain's government, after making concessions to voters and a left-wing party, are slim.

Today, David Cameron’s coalition government reached its first 100 days in power. FrumForum is marking the day with an online symposium. We asked our contributors: can anything “new” in Cameron’s conservatism survive this fiscal crisis? Click here to read more responses.

For a conservative, a fiscal crisis should be the kind of crisis that shouldn't go to waste. When the state is broke, conservatives should shrink it. Unfortunately, the historical record shows that this never happens.

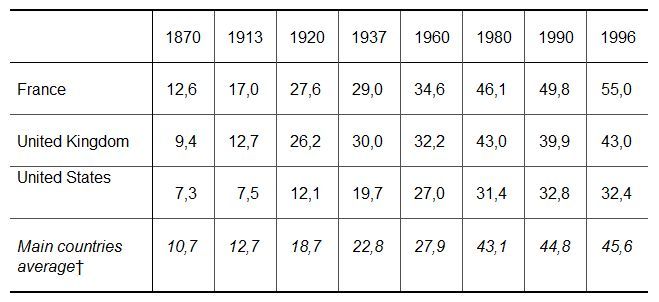

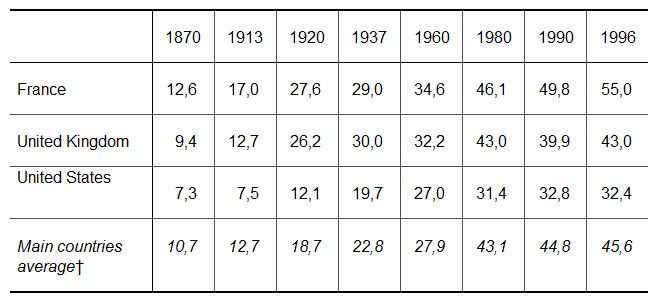

Here is the evidence. This table shows the weight of the state in GDP percentage from 1870 to 1996 in the main Western democracies, and how the size of the state did not decline during conservatism’s high water marks.

Source: Vito Tanzi et Ludger Schuknecht, Public Spending in the 20th Century. A Global Perspective, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 6-7, quoted here in a paper by Pierre Lemieux.

Source: Vito Tanzi et Ludger Schuknecht, Public Spending in the 20th Century. A Global Perspective, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 6-7, quoted here in a paper by Pierre Lemieux.

† That is: Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Ireland, Japan, New-Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, Belgium, Netherlands, Spain

The table shows that Thatcherite conservatism resulted in an unimpressive 3.1% drop in the percentage of public spending and that the United States oversaw an increase of the weight of government under Reagan. In other words, the two leaders that are supposed to have shrunk government left their respective countries with an economy that was still more state-run than any Western democracy in 1960. In spite of the intellectual revolution that started in the 70s and resulted in many free-market reforms, the state has not backed off an inch.

Politicians of all stripes are unwilling to reduce the size of government if it involves giving up power. The state used to be primarily concerned with its military and ability to wage war. Then in the mid-twentieth century European states stopped making war and let the defense budgets shrink to spend more on healthcare systems, social transfers wealth redistribution, "cultural" policies and so on. Some intellectuals knew exactly how to justify this. Keynes argued that collecting and spending money was not only necessary in some cases, it was actually good for the economy. That was absurd but politicians liked it.

Government growth now occurs neither for military or economic necessity but because politicians like it. Businessmen try to acquire wealth and politicians try to gain power. The difference between wealth and power is that wealth can be created out of nothing while power cannot. This is why competition for power gets a bit testy in some historical contexts. Western democracy made it more civilized but the basic principle remains the same.

Politicians have found creative ways to justify more growth in government. Ironically, one method is decentralization. Scotland’s recently acquired autonomy has probably made many local Scottish politicians very happy. In France, a huge process of decentralization started in 1982 and resulted in an enormous expansion of local budgets. Decentralization allows local politicians careers running local "territories" - councils, departments, regions - with a huge increase in local administrative personnel. Some members of Parliament keep their seat for thirty years or so, along with the presidency of a local council or two.

Another way to increase political power is to expand the central state's attributions. This was done in France in 1981, when the socialists nationalized large chunks of French industry and used it to secure appointments for members of the party. The so-called conservative opposition went back to power some years later but despite their ostensible rejection of socialism, the state and the local governments did not shrink at all. Conservatives ended up putting their people in places of power.

European economies are currently faced with a fiscal crisis that results from the fact that the public debts are roughly of the order of one year's global product. One could see the current situation as an occasion for conservatives to impose radical free-market policies and cut state spending for good. That, however, will prove difficult.

As long as politicians, conservative or not, owe their political success to people they have to reward they will use public resources to do that. The probability that a professional politician like Cameron, who made a lot of intellectual concessions in order to get elected and then had to accept compromise with a left-wing third party in order to form his cabinet, will force massive cuts that will make a lot of people unhappy is not very high.