Bernanke's Toughest Job: Selling the Fed

Next week, Ben Bernanke will do something no Fed Chairman has ever done before: hold a press conference after the conclusion of the Fed’s FOMC meeting. Ostensibly this is “intended to further enhance the clarity and timeliness of the Federal Reserve's monetary policy communication.” The Federal Reserve is often criticized for being a secretive institution and its quantitative easing program has not been popular with some conservatives. But can a press conference really help Bernanke fight back both of those impressions? Or is this largely just damage control to prevent his voice from being drowned out by criticism?

While the Fed is criticized for being an institution that avoids transparency, it’s important to note that progress has been made in increasing openness, and that this hasn’t necessarily been accompanied by an increase in trust in the institution. Bernanke’s press conference builds on other efforts by the Fed to increase transparency; the Fed began announcing changes to the interest rate in 1994, and then began to expedite the process by which it would release its FOMC minutes in 2004.

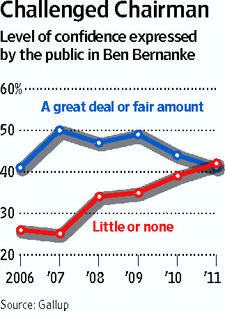

Yet current anti-Fed sentiment is likely at an all-time high. In 2003, Gallup found the Fed approval rating at 53%; in July of 2009 (before Lehman Brother’s bankruptcy) it was at 30%. This chart from Gallup printed in the Wall Street Journal, shows the decline in confidence in the chairman:

Especially since the financial crisis, Congress has demanded more transparency from the Fed. Don’t forget the House voted for an audit of the Fed and that a more watered down one-time audit of the Fed passed the Senate as well. So it’s unlikely that more press conferences from the Fed are likely to reduce demands on the Fed to be more open. This attitude will persist as long as the economy remains weak.

So the press conference may not help with the Fed’s overall image, but can it help deal with the specific critiques being leveled at the Fed’s actual policies such as quantitative easing? Probably not as long as the Fed’s opponents are unilaterally opposed to Fed's policy.

Alan Meltzer, a historian of the Federal Reserve at AEI, tole FrumForum that Bernanke is acting partly because he faces pressure from a “Republican Congress, and an oversight committee headed by [a] congressman who is hostile to what the Fed is doing.” Meltzer was of course referring to Ron Paul, and since Rep. Paul wishes to “End the Fed” it’s unlikely that any press conference Bernanke gives will have an impact on how he runs the committee.

This sort of skepticism is pervasive in parts of the right. When the Bernanke press conference was announced last month, Judge Andrew Napolitano’s segment on Fox Business discussing it was both dismissive and arguably also mocking in his description of Ben Bernanke as an out of touch academic:

How realistic should our hopes be that we’ll get closer to an audit or find out what they are really up to, or will the former Princeton professor [Bernanke] whose use of the English language is very glib and sophisticated, just dance around questions and not give us serious answers.

Unless Bernanke makes a remarkable or unexpected concession during the press conference (such as claiming that the rise in commodity prices has indeed been his fault) it’s likely most Fed critics will be unsatisfied with his answers.

If the press conference won’t help the Fed’s overall transparency, or diffuse criticism over its policies, then what is its real point? Meltzer noted in the interview that Bernanke is facing since “many of his colleagues think he is wrong.” Indeed, other Fed Presidents frequently give media appearances where they suggest the current Fed policy is wrong. The Wall Street Journal recently summarized some of these views:

In the past month alone, 16 different Fed policy makers have given more than 40 formal addresses, in addition to television, newspaper and newswire interviews. They espouse different views, not only on when to reverse the Fed's easy-money policies, but how.

Mr. Bullard wants to stop the bond-buying program early. Charles Plosser, president of the Philadelphia Fed, wants the Fed to move quickly to sell its bond holdings. Mr. Hoenig has been pushing for interest-rate increases for months. The dissonance is in part the result of the complexity of the situation. "We can't speak with more certitude than we have," said Mr. Rosengren.

Some traders think the Fed carefully scripts its messages with regional-bank presidents. In fact, it is often just the opposite.

Some officials at the Fed board in Washington have been annoyed that regional bank presidents are staking out policy positions before the policy-making Federal Open Market Committee even meets to consider them. They also have been concerned that Fed chatter after meetings might be confusing the public about the Fed's actual plans. The Fed comprises 12 regional Fed banks and a board of governors in Washington, with five of the regional-bank presidents voting on interest-rate decisions on a rotating basis.

Bernanke may not be able to change the public’s perception of the Fed, or appease critics who don’t believe in the institution he runs, so perhaps the least he can do is try not let his voice be crowded out by others in the media.

Follow Noah on Twitter: @noahkgreen

Tweet