Belarus Nears Economic Collapse

MINSK, Belarus — The waiting list outside a currency exchange office at the Korona supermarket here had swelled to 52 people and many were getting desperate. Some had been waiting for three days, sleeping in cars, in an increasingly frantic effort to get dollars and euros.

This former Soviet republic is on edge. Prices are rising and theBelarus ruble, the national currency, is shedding value. Already some imported foodstuffs have begun to disappear from store shelves, people here in the capital say.

Though the extent of the current crisis is not yet clear, a sense of foreboding is spreading, compounded by the mysterious bombing last week at a subway station here that killed 13 people and wounded nearly 200.

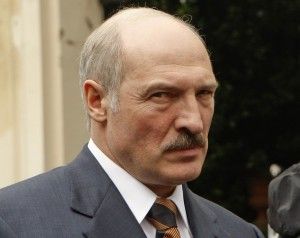

The attack appears to have shaken confidence in Belarus’s longtime authoritarian president, Aleksandr G. Lukashenko, who claims to be the country’s sole guarantor of security and stability. Still, the latest economic travails could prove to be even more challenging.

In post-Soviet countries like Belarus, there are few starker indications of crisis than people waiting in lines, and the appearance of crowds gathered outside currency exchange offices has rekindled memories of shame and privation from the years just before and after the Soviet collapse in 1991.

Even before workmen had cleaned away the last rubble from the bomb’s destruction at the Oktyabrskaya subway station last week, an unmoving line had formed at a currency office just a short walk from the site of the attack.

“You remember the 1990s when people waited in line for bread,” said Maria Titova, 40, a housewife, who had been in line at the Korona supermarket for several hours. “Now we wait in line for dollars.”

The scramble for hard currency has been driven in part by fears of an impending devaluation of the Belarus ruble, which the government keeps at a fixed exchange rate. Yet even under normal circumstances people here favor foreign currency for major transactions.

Of all the former Communist bloc countries, Belarus has perhaps the closest resemblance to the Soviet Union. With its strong-arm president and robust security service — still called the K.G.B. — this country of 10 million is easily the most autocratic in Europe.

In nearly 17 years as president, Mr. Lukashenko has created a centrally planned economy based on the Soviet model, while stifling independent enterprise. Though his supporters credit him with sparing Belarus the wild economic fluctuations experienced in neighboring Russia and Ukraine, opponents say the system has created nothing but stagnation.

These days, Belarus is largely dependent on foreign handouts to stay afloat. Angered by apparent fraud in December’s presidential election and a sweeping crackdown on the opposition that followed, Western governments have imposed sanctions against Mr. Lukashenko and his government and all but cut off relations.

And now, Mr. Lukashenko’s two main donors, Russia and the European Union, seem to have deserted him.

Russia’s leaders, who have clashed frequently with Mr. Lukashenko in recent years, have said they are considering a $3 billion loan to help alleviate the current strains. But experts here say Russia will most likely demand painful concessions in return.

Meanwhile, Belarus’s foreign reserves have fallen by over $2 billion to just $3.7 billion from a high point last October, according to the International Monetary Fund.

The dwindling reserves prompted Standard & Poor’s to lower Belarus’s long-term foreign currency rating last month.

The Central Bank has now been forced to limit the availability of hard currency. Most of the dollars and euros still available can be purchased only on the black market at elevated exchange rates, people here say.

“I sell products calculated with a specific exchange rate, but now I cannot buy dollars at that rate because there are none,” said a cosmetics salesman named Oleg, who had spent the night in his car outside the Korona supermarket. “I am working in the red.”

Click here to read more.