An American Warrior in an African War

FrumForum contributor Sean Linnane is hard at work on a novel. This Memorial Day, we present the prologue to his latest work:

As a map, the continent of Africa resembles a skull; the fossilized skull of some primitive sub-human ancestor from deep within the dust and debris of Uldabi Gorge. If one starts at the straits of Gibraltar, where Africa comes closest to Europe, and traces a finger southerly, the western coastline of North Africa curves around to the base of the skull. On a human this is the medulla oblongata, where the spinal column joins into the most primordial part of the brain, the part of our being that governs instinct and involuntary muscle movement. On the map this is West Africa: an irregular, variegated coastline. Its solid green represents the low altitudes, dense vegetation, mosquito infested jungle, primordial scum.

Abidjan, Ivory Coast - Cote d’Ivoire - is a modern city on the edge of the West African coastline. Built on islands in an inland system of hyacinth-covered, crocodile- and hippo-infested lagoons and surrounded by emerald forest-covered hills, her modern skyline rises like a fantastic set from some science fiction epic.

The press had been harping about the “riots in the streets of Abidjan” for weeks, but the few clashes I saw out there didn’t come anywhere near what I would classify as a fully-fledged riot. More like spirited demonstrations, almost staged events for what it was worth.

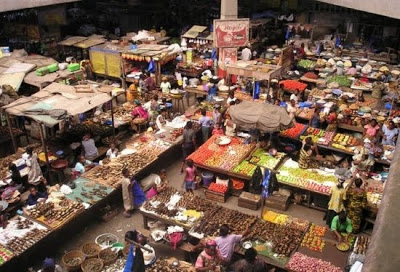

There is no discernible beginning or end to the souk in Abidjan. There is no parking lot, no clearly marked entrance. The roadside stands simply increase in number as one approaches the area of the souk; merchants selling clothing, fruit, shoes, handbags, magazines, masks and African animals of carved wood or semi-precious stone, everything and anything imaginable.

Every hundred meters or so one encounters a woman standing by a large enamel or plastic basin perched on a barrel or a drum, full of antibiotics and other miscellaneous pharmaceuticals acquired from black market sources or the careful gleaning of westerner’s rubbish. Customers sift through the medications, lift up containers of pills in bubble packaging or plastic pill bottles with typed prescription labels to carefully inspect the mysterious drugs until they find something they feel will remedy whatever it is that ails them. Along a street that sells wooden artifacts one may find stall after stall selling hundreds of small statuettes featuring white men dressed as doctors, policemen, soldiers. Hopeful patients can place such statuary in their home, burn candles and offer liqueur, tobacco to the image. This is gri-gri; juu-juu or voodoo. If the pills don’t work, a gri-gri doll will.

The center of the souk is in a crumbling shell of concrete that goes up at least three stories; I never determined how far the complex goes in laterally. The roof in some places is made of the same steel-reinforced cement as the walls, mostly however the merchants stretch swathes of cloth between the walls to provide shade from the sun. The floor beneath one’s feet is sand, the interior is maze-like. A narrow set of stairs goes up the side of the building; merchants are tucked into every nook and cranny, poking out to offer their wares as one passes by.

It is hot and humid, airless within the depths of the souk. The senses are assaulted by a barrage of sights, sounds and smells. Bolts of vividly colored printed cloth, stalls featuring thousands and thousands of colored glass beads, more wooden statues and carved animals; hippos, crocodiles, warthogs, rhinos, gazelle, elephants, lions, zebras. Animals made of the printed cloth. Suitcases and shipping trunks. Hand tools, made in Taiwan. Korean mink blankets featuring Oriental geometric patterns or the old favorite, the white Siberian snow tiger, stacked to the ceiling in their vinyl packaging. West African music, the ancient ancestor of rock and the blues, blares it’s hypnotic rhythms out of cheap boom boxes and ancient transistor radios; the air reeks of spices, fruits, perfumes, the smell of dusty wood, and always, everywhere, the smell of thousands of sweating bodies.

A niche in the wall features shelf after shelf of ivory; tusks, statues, bracelets, bangles, necklaces, earrings, rings. More ivory lays beneath glass display cases. The owner is an ancient black man in purple robes. He wears a fez, his eyes have a wisdom that is a thousand years old. He puts his hand on mine, draws me close. His dark skin looks almost blue against my arm. “Monsieur,” he says quietly, displaying a mouthful of stained and rotting teeth. “Today is not a good day for you in the streets of Africa.”

More to come...

Originally published at STORMBRINGER.

Tweet