America's Greatest Superhero Turns 70

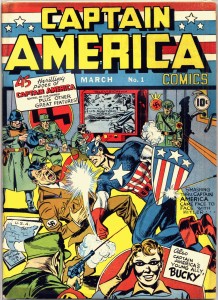

It remains the most memorable blow ever struck for liberty in the history of American popular culture. When the first issue of "Captain America Comics" appeared on newsstands 70 years ago, the cover depicted a flag-draped symbol of young American manhood administering a crushing uppercut to Adolf Hitler's jaw.

It was a knock-out blow to fascism delivered by the giddily idealized embodiment of American virtue. And it gave vicarious expression to the impulses of a country where the public mood had been on a war-footing for months.

Cover dated March 1941, the crude but galvanizing imagery amounted to a declaration of war on Hitler, a full nine months before the Führer declared war on the U.S. in the days following Pearl Harbor.

At a time when isolationist voices were still cautioning against American involvement in another European war, this was FDR's pro-war case rendered in four primary colors and reduced to its essentials.

As Captain America vaulted into the Berghof, he interrupted Hitler watching a U.S. munitions plant being dynamited by fifth columnists on a TV screen. The Eagle's Nest, littered with logistics maps showing his sinister territorial ambitions on America, delivered a message with all the subtlety of Cap's jaw-breaking haymaker: Hitler was not just the mortal enemy of European civilization--he was America's mortal enemy, too.

The cover art ensured the book sold out in days. The dynamic stories inside in which careening, non-stop action threatened to burst out of the restrictive panels, ensured readers came back for more. Super-patriotism and super-heroism proved an unbeatable combination. The second issue of "Captain America" had a print run of more than a million copies.

In 1941 the comic book industry was as very youthful as the audience it appealed to--an audience aware it would soon be donning uniforms and being called upon to perform Captain America-style acts of derring-do against the Axis.

Superman had rocketed from Krypton into the national consciousness just three years previously. Batman had only started stalking Gotham's City crime-haunted streets in 1939. Comic books featuring the two characters (no one called them super-heroes yet) sold millions of copies a month. What's been described as a "mushroom-growth" of rival New York publishers appeared almost overnight, all trying to replicate National Allied Publications' phenomenal success. Nothing worked. Dozens of long-underwear characters appeared on newsstands and just as quickly disappeared. The would-be contenders could have inspired the Charles Atlas campaign, a fixture of comic book advertising for decades. Yet they were all 97-pound weaklings compared to National's twin titans. Until Captain America bound past a Gestapo bodyguard to deck the Führer.

Captain America was co-created by New York cartoonists Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. There had been an earlier comic book super-patriot (The Shield) and Captain America's success ensured there would be dozens more in an industry where plagiarism was and remains every bit as much the prevailing “ism” as in Hollywood. But none could compete with Captain America's unbounded vitality, unembarrassed love of country and, most crucially, the sense of near-universal identification he inspired. That's because the character amounted to an almost primal exercise in wish-fulfillment on the part of co-creator Kirby.

Kirby was a compact and socially awkward man intent on escaping from Hell's Kitchen armed only with a pencil and a seemingly boundless imagination. Born Jacob Kurtzberg, this son of Austrian Jewish immigrants legally Gaelicized his name, partially for professional reasons, partially as a tribute to his idol Jimmy Cagney -- another scrappy bantamweight from New York's Lower East Side. Largely self-taught, he began selling his work professionally while still in high school.

Collaborator Simon has been credited with creating the concept and look of Captain America. But 21-year-old Kirby provided the animating spark. The division of labors between the two men was always blurred – working to deadlines almost as foreshortened as Kirby's trademark figures, they both wrote, edited and drew. But "Captain America" – the first title which allowed free rein to his full creative energies – was always more informed by Kirby's frenetic visual style, breakneck pace, and almost berserker-type rage when it came to bullies, thugs and bigots, a rage he largely sublimated in his daily life but which overflowed into his artwork.

Captain America began as 4-F Army reject Steve Rogers, before being transformed by a refugee German Jewish scientist's potions into a "super-soldier". But he had no super powers, per se. Rather, his frail form was amped up to the peak of human abilities (those who either volunteered or were drafted would soon undergo similar physical transformations – by way of boot camp rather than mysterious serums).

After a Nazi assassin kills the formula's creator, Rogers is left as America's lone super-soldier. Recognizing his value as a propaganda weapon as well as a weapon of war, he is outfitted in the flag by his military handlers, his chain-mail shirt and shield intentionally reminiscent of a crusader's. Then he is dispatched to fight Nazi spies and saboteurs and their Axis allies.

No longer ineligible for military service, he serves undercover in the ranks as a no-longer sickly but still put-upon Private First Class Steve Rogers. But once he dons his star-spangled uniform, he goes from schlemiel to Übermensch. Routinely abandoning his post to take America's colors into battle against the Axis as Captain America, PFC Rogers just as frequently finds himself assigned to KP duty for missing roll-call. Every grunt would soon identify with the military's dual emphasis on individual initiative and strict routine. Every grunt lived in hope that slipping into a uniform would turn him into a hero.

Kirby and Simon worked on "Captain America" for a year before a royalties dispute with publisher Timely (forerunner of today's Marvel Entertainment Group) prompted them to decamp for National.

In 1943 Kirby was, as he said, "handed an M-1 and a chocolate bar and told to go kill Hitler". He followed in his most enduring creation's footsteps, putting on a uniform sporting an American flag shoulder patch rather than wrap-around red and white stripes, and marched off to war. He arguably never took those army fatigues off again until the day he died in 1994.

A member of George Patton's Third Army, PFC Kirby landed on a body-strewn Normandy beach ten days after D-Day and spent the next year under fire as Allied forces pushed towards the German frontier. He came to hate war as only a combat veteran can. He witnessed both battlefield carnage and the atrocities which had taken place behind the wire-fencing of a concentration camp. He was haunted by nightmares about World War Two for the rest of his life.

Kirby partially exorcised his demons by way of his prodigious post-war output. For more than four decades he refought the war in literally thousands of comic book parables which pitted moral absolutes against one another kitted out in Western, gangster and super-heroic drag. In the process he became comics' most celebrated – and prolific – creator, his personal visual motifs co-opted as the industry standards. He resurrected Captain America – mothballed after the war – even while creating or co-creating the current roster of Marvel's upper-tier characters in the '60s with editor Stan Lee (the office boy during Kirby's first go-round). The revived Cap has arguably never been better served since Kirby returned him to his original setting for a series of retellings of his wartime exploits.

"Hitler had to be destroyed, there was no choice and I was glad to do my duty ...," Kirby once said, adding his abhorrence for war never blinded him to the fact while it is always an evil, in the case of the Axis it was very much the lesser of two evils.

A self-identified New Dealer and a lifelong liberal, Kirby would have scoffed at the idea conservatism played any role in his thinking or his storytelling. But it did.

Captain America was created as a direct response to the prevailing spoiling-for-a-fight national mood. Commercial considerations played every bit as much of a role in his origin as his creators' patriotism. But Kirby's take on the character, fusing an innate, inchoate conservatism with an immigrant's passion for defending the freedoms and opportunities America provided, resonated precisely because it was so visceral it could never have been counterfeited.

That striking-a-blow-for-liberty cover of the first "Captain America Comics" remains instantly familiar today even to those who have never cracked a comic book. It's been endlessly reprinted and parodied (Joe Simon himself produced a take-off featuring Cap flooring Osama Bin-Laden after 9/11). Homages have been paid in all manner of media. In 2000 its imagery provided the point of departure for Michael Chabon's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel "The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Klay" (Chabon's dedication ends: "Finally, I want to acknowledge the deep debt I owe in this and everything else I've ever written to the work of the late Jack Kirby, King of the Comics" ). Doubtless the iconic punch will feature in the upcoming "Captain America: The First Avenger" summer blockbuster.

There seems to have been a case of mistaken secret identity when it comes to Captain America. Forget PFC Steve Rogers. Cap's real alter ego was PFC Jack Kirby.

Tweet